Thomas Edgar During The Hong Kong War: A Chronology

Part 1: the fighting (December 8-25, 1941) and internment in the Lane Crawford Headquarters (Exchange House) and the French Hospital in Causeway Bay

Key to references:

BB = article by Thomas Edgar in The British Baker, September 13, 1946 (wrongly attributed to ‘E. Edgar’)

UPB = unpublished manuscript of British Baker article.

BE = recollections of Brian Edgar

Herklots = Food and War in Hong Kong by Dr. Geoffrey Herklots in Nature, March 16, 1946.

NTSC = Not The Slightest Chance: The Defence of Hong Kong, 1941 (2003) by Tony Banham

Chronology = Chronology of Thomas Edgar’s life drawn up by Wilfred Edgar in the mid 1980s. This Chronology is a continuation of this work.

Pre-war Letter, 1 Letter to family Windsor, probably written in late November, 1938.

Pre-war Letter, 2 Letter to family written in early February, 1940.

Post-war Letter, 2 Letter to family dated October 17, 1945.

Details of other sources are given on first citation.

1938 TE falsifies his age and moves to Hong Kong to work in a managerial capacity for the bakery of Lane Crawford, an important Department Store.

A report in the Windsor and Eton Express (late November or early December 1942) states that he went to Hong Kong in April 1938, and this probably reflects information provided by his parents. He sailed on HMS Carthage.

He lodges at 82, Morrison Hill Rd.[2] He says in a postcard to his sister Joyce[3] that his lodgings overlook Happy Valley Racecourse and he can watch the pony racing for free.

1938, May 30 According to an account in the Hong Kong Daily Press the Chairman of Lane Crawford reports to the Ordinary Yearly Meeting held at Exchange House (see below) that the company have acquired ‘commodious and eminently suitable premises’ for a new bakery. The report continues: ‘I confidently affirm that – when completed – the new bakery will be without equal in theFar East in the manufacture of bread, cakes and confectionery under the most efficient and hygienic conditions’.

November 26, 1938 A Lane Crawford ‘advertorial’ in the Hong Kong Telegraph announces the transfer of their bakery from Burrows Street in Wanchai to larger premises in the Happy Valley section of Stubbs Rd.[4]

1938 October-November TE receives letter telling him not to join Volunteers but to ‘keep the bakehouse ready for any emergency’. He reassures his family that ‘every where is gas proof’ – this seems to include the bakery and perhaps it is only the bakery referred to.[5] TE was lucky: ‘most able-bodied men were automatically members of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps’[6] and conscription was introduced in 1941. These men were mobilised on Sunday, December 7, and many were killed in the fighting. If he’d survived TE would have been interned under the harsher regime of the POW Camp at Shamshuipo (and would never have met EE – see below).

TE has bought dressing gowns and table cloths and wants to find a way to send them home; he’s bought a lot as he doesn’t think they’ll be many around soon: ‘when the Japs come they will take the blooming lot’.[7]

1939 TE’s name appears in the Hong Kong Jury lists for the first time.[8]

1939, February TE went on an outing to Saukiwan with three other Lane Crawford’s employees – Jean, Charlie and Sammie.[9] This may be the same Jean who has written to TE’s home in Windsor and perhaps also sent a jade brooch and some cushion covers.[10]

1940 February 20 The Hong Kong Telegraph reports, under the heading ‘Latest’, a large win for the Lane Crawford Bakery Department on the Hong Kong Derby Sweepstake. In a letter home he states that his personal share was worth about £650 in British money – about £26,000 of purchasing power today, although closer to £90,000 measured by the change in average earnings.[11] He sent £100 home immediately. The win did cause some problems: he believed that he would have to train new staff, as the Chinese workers all planned to move to the part of China close to Macao and buy land to grow rice.[12] He used some of the money to buy three trunkfuls of Hong Kong artefacts, all of which were looted during the war.[13]

1940, April 5 Accepted into the Eastern Scotia Lodge (Freemasons).[14]

January 13, 1941 telegram home: Many Happy Returns.[15]

April 6, 1941 TE and his friend Tommy Waller, an engineer on the Peak Tram, go out to the Prison Officer’s Club at Stanley Prison and play darts with R. E. Jones, the Hong Kong hangman (Diary of R. E. Jones).

Autumn-Winter 1941 TE, Mr. Meredith and Dr. Herklots working on a ‘siege biscuit’. – ‘we got on well Tommie and I in those hectic pre-war days’.[16] Production by late October is 1.5 tons of biscuits a day.[17] Dr. Herklots later wrote:

With the enthusiastic co-operation of a master baker and after about thirty trials, it was found possible to make a hard siege-ration biscuit from this {peanut} meal and whole wheat flour… The biscuits contained only 2 per cent water, and they were packed in petrol tins which were then sealed. On the day before the Japanese attacked, a satisfactory biscuit was made which contained added calcium carbonate and shark liver oil. Everybody liked the biscuits – all nationalities and all ages from six months to over eighty years….[18]

December 7 The Hong Kong Volunteers are mobilised. TE’s probable staus is Volunteer ‘seconded to Essential Services’ and he might have been sent to the bakery at this time.

December 8 Japanese attack on HK begins. The first air raid is at 8 a.m. TE is almost certainly already at the Bakery inStubbs Rd.

TE appointed Deputy Supplies Officer Bakeries, bringing all bakeries on HK Island and in Kowloonunder his supervision. He’d probably already decided during the three year period of preparation to keep the Bakery in Stubbs Rdworking and open other bakeries as and when required. Daily output of bread was 16,000-22,000 pounds.[19] After a few days he also takes charge of the RASC (Royal Army Service Corps) Bakery.[20]

TE sleeps in office chair (later camp beds are acquired). He spends most of his time either in Lane Crawford’s or in various Chinese bakeries (almost certainly including the Green Dragon (Qing Loong) in Wanchai).[21] Essential service Workers had the right to a free lunch at the Café Wiseman,[22] but it is not known if TE went there to eat. At some point he tears up his shirt to dress the wounded,[23] but it is not known if this was in Lane Crawford’s bakery, one of the other bakeries, or in the Lane Crawford HQ where he was sent after surrender. There was an Emergency Centre that treated the wounded in the Gloucester Hotel, next to the Lane Crawford HQ,[24] so this is also a possible location.

December 13 By about 8.30 a.m. the Japanese are in full control of the mainland (New Territories and Kowloon).[26] From now until the surrender the Stubbs Rd. Bakery is ‘in the direct line of fire between the Japanese and our own troops’.[27]

December 15 Production of siege biscuits discontinued.[28]

December 18 On a wet night, with the north shore of Hong Kong island covered in smoke from fires, the Japanese begin to cross the harbour from Kowloon and land on the Island to begin their final assault.[29]

December 19 The Army Bakery at Deep Water Bay is captured and the army authorities gave TE orders to increase production by 4,000 pounds per day. They also sent two members of the RASC, Hammond and Sheridan to assist TE. Hammond later baked with TE in Stanley,[30] while Sheridan escaped from H.K., winning a Military Medal.[31]

After the capture of the North Point Power Station[32] there is no electricity or water in the Stubbs Rd. Bakery.[33]

The Japanese army had landed on the north-east coast of Hong Kong Island, as the distances across the harbour there are shorter; they then pressed southwards and westwards, seeking to capture the north-south running Wongneichung Gap, cut the island into two halves. and then to force the British surrender by moving westward and conquering the administrative and business heartland of Hong Kong, the district then known as Victoria (now Central).[34] These operations were taking them closer and closer to the bakery, which was somewhere in the HappyValley district.

Leighton Hill – to the north east of the Race Course – was an important British strong point which finally fell on December 24th, soon followed by Morrison Hill (N. E. of the Race Course – according to Google Earth this battle was going on 39 metres from TE’s lodgings at No. 82) and Mount Parrish [35] This left the road to Victoria open – hence the surrender on the 25th.

But before that happened the fighting had got too close and TE’s work in the Stubbs Rd. Bakery had come to an end.

December 21 TE decides the Stubbs Rd. Bakery is now untenable:

I then decided to open five smaller bakeries and decentralize. I had already stocked various bakeries with wood, flour and hops (Yeast would not keep out of a refrigerator in such a hot climate.) The Fire Brigade delivered water to the bakeries twice a day in a fire float.[36]

It is not known where these bakeries were. TE regarded the Green Dragon Bakery in Wanchai (see below) as the best of the Chinese bakeries, This could have been one of the five he opened, but on the December 21 and 22 the defenders were being pressed hard in Causeway Bay[37] (to the east of Wanchai) so, unless it was in the western part of Wanchai it wouldn’t have been viable for long, and might never have been opened at this time.

December 24 By now Hong Kong is a ‘sea of fire’; sanitation has broken down, and every building stinks. The invaders are in the Wanchai district, where there is some of the bitterest street fighting of the war. Wherever TE is – in Stubbs Rd or in one of the five smaller bakeries – the fighting is getting close.[38]

December 25 A ‘clear and bright’ dawn’[39] on the last day of British rule in Hong Kong. Soon after 3 p.m., the British surrender.[40] The noise of shells, bombs and rifle shots is replaced by silence.[41] All Lane Crawford Staff are told to report to Lane Crawford HQ,[42] The Exchange Building at 14, Des Voeux Rd.[43]

TE might have arrived in time for Christmas Dinner – the Café Wiseman, the Exchange House restaurant, served turkey and plum pudding after the time of the surrender on Christmas Day[44], and had a Christmas tree.[45] He probably walked to the Exchange Building with other Lane Crawford staff; if he was on his own, he would probably have been robbed of his watch and other valuables by gangs of looters,[46] and both he and EE sold their watches in Stanley Camp, so presumably avoided looting.

TE took part in pouring away alcohol so that it would not further inflame the Japanese invaders.[47] This was possibly at the Gloucester Hotel, which was very close to the Exchange Building: after the surrender, it was decided ‘that all liquor in the hotel must be destroyed’ and ‘over $50,000 worth’ was broken up and poured down a bath room drain’.[48] This job was given to the police, ‘aided by many volunteers’:

Because drains were blocked, and there was no water to wash it away, it (which includes champagne, whisky, gin and anything else you can think of) began to run down the staircase. The whole place reeked.[49]

John Stericker also records that the atmosphere became alcoholic, and that the police disposed of some of the liquor by drinking it, as did TE.[50]

However, it could be that TE’s work pouring away alcohol took place at the Exchange Building itself as its café (see below) had a liquor license, as did the Soda Fountain Restaurant, which was also very close.[51] It is of course possible that TE volunteered for liquor duty at more than one location.

The lane between the Exchange Building and the Gloucester Hotel had been nicknamed ‘Blood Alley’ as it was the place where the Hong Kong Police executed those caught looting during the fighting.[52]

December 26. The Japanese take control of the Exchange Building. The Rising Sun flag was soon flying over the Exchange Building, but so were two white sheets, which seem to have been raised earlier as a sign of surrender and not immediately taken down.[53]

The officer in command of Lane Crawford’s is Captain Tanaka, a humane man.[54] He gives TE permission to return to his lodgings to get a new shirt.[55] This is an important act of kindness as the weather was already bitterly cold[56] and remained so through February.[57] He confiscates his binoculars but gives him a chit for them, saying the Japanese army will compensate him for the loss after the war.[58] During the period of internment in Exchange House, Tanaka sometimes arranges film shows for the internees (and for his soldiers, who are billeted there).[59] The venue for these shows was the Café Wiseman.

The Café Wiseman had been the centre of the Hong Kong telephone network during the war,[60] and the staff of the Telephone Company were also interned there – ‘and treated well by a Captain Tanaka who was in charge’.[61] They were given ‘good food’ and managed to gather together ‘all kinds of useful tinned stuff and foods’,[62] so TE probably was probably well fed at this time, and might also have managed to scavenge some tinned food from the Café or the Lane Crawford Department Store.

The staff of the Telephone company were civilians and so were told that they would be interned in Stanley, but ‘(u)nfortunately a uniform was found at the last minute’ and they were sent to the military internment camp at Shamshuipo, were conditions were tougher. Once more, TE, who had been baking alongside army bakers, was lucky.

The senior Telephone Company engineer, Robert Farrell, who was married to a Spanish woman and was Spanish Consul, successfully claimed Irish nationality while at the Exchange Building. He and his wife and baby managed to get out of Hong Kong, and he returned to the Colony with the rank of major, on about September 10, 1945.[63] Note: Farrell went to Macao with Japanese permission, and escaped from there. His son, R. C. Farrell, became an executive director of the HKSBC. (Frank King, History of the HKSBC, Volume 3, 667.)

The Japanese brought Kane Bush to Exchange House to act as interpreter. She was a Japanese woman who’d married a British volunteer sailor: a brave and humanitarian woman, she was later arrested herself and eventually sent back to Japan where she was persecuted by the Kempetai and her fellow citizens.[64]

At some point, Tanaka also gave Selwyn-Clarke permission to distribute the ‘siege biscuits’ to the camps and hospitals: ‘Those vitamin biscuits were of real value’.[65] Some biscuits remained and were eaten after liberation from internment:

(T)he biscuits when we came out of Stanley Internment Camp in 1945 were in excellent condition and 2 * ½ oz. biscuits contained enough B.1, B.2, Iron and Roughage for one day.’[66]

‘Vitamin’ biscuits were sent daily to William Anderson, when he was in Stanley Prison (late 1943- June 22, 1945) although the Japanese didn’t always give them to him. There were probably attempts to get them to other prisoners, as their diet was even more limited nutritionally than that of the internees.[67]

Selwyn-Clarke records the rumour that Tanaka was later executed for his kindness to the prisoners (there was another Tanaka in Hong Kong who was executed after the war for crimes against both Allied and Chinese nationals).

At some point TE was introduced to a Eurasian woman, Evelina Marques d’Oliveira. (henceforward EE). The introduction was made by EE’s landlord, probably the Swiss national Robert Bauder, who also worked for Lane Crawford and was a friend of TE. Bauder believed that TE could help EE find something to eat – most probably he took her to the Ching Loong Bakery to get bread. Eventually, an engagement ring was bought, which was sold in Stanley to buy food.[25]

During this period and the subsequent one, when he was interned at St. Paul’s (‘the French’) Hospital TE would have needed an ‘enemy alien’ pass, which would have given him some freedom of movement.[68] Other internees have reported that they were sometimes able to escape Japanese control and visit places without authorisation,[69] and Emily Hahn reports that, after the first months the Japanese relaxed their restrictions relating to enemy presence on the Peak and allowed free access to the (heavily guarded) Japanese-style tea pavilion close to the exit point of the funicular (tram).[70] However, it’s probable that TE’s movements would be far from free: Ellen Field reports that, in order to visit her at home, Selwyn-Clarke had to make up a story to account for his absence.[71] On one occasion T. E. was questioned by Japanese soldiers about his presence outside a place of interment; according to EE (see below), they trusted his answer because he admitted at once to being English instead of claiming to be Irish.[72] (The Irish were neutrals and so not interned; at least four people, one of them TE’s fellow baker Sheridan,[73] had claimed to be Irish even though they had British passports.)

Whenever he left either the Exchange Building or The French Hospital – whether for work or other reasons – he would have been liable to see horrific scenes of Japanese violence against the Chinese.[74]

January 4/January 5, 1942 Enemy civilians are summoned by the Japanese to present themselves at the Murray Barracks Parade Ground in Victoria (now Central).[75] They are taken off to hotels/brothels on the waterfront. TE, two other bakers, some volunteer drivers, medical and banking personnel are exempted from this process.

January 9[76] Tanaka gives permission to resume the baking of bread for the hospitals, and TE opens the Green Dragon Bakery in Wanchai, probably the biggest and best of the Chinese owned bakeries.[77] At first production is 590 lb. of bread probably per day), later this is increased to 3,000 lbs. per day.[78]

Later on we were interned in the French Convent (sic – a mistake for Hospital). and as we had plenty of rice I got a dealer to grind some on a Chinese Stone Mill and added ground rice up to 60% of the flour. The yeast we were using was made by boiling 1g hops in 1 gallon of water for forty minutes then adding the mixture to 1-lb. flour that had already been slackened down with cold water. This we kept going for about two years until our stock of hops ran out. Then we made quite a good yeast from sweet potatoes using the same method only using 1-lb sweet potatoes instead of 1g hops.[79]

Barbara Anslow:

How welcome was the meagre bread ration we received in Stanley in the early days. It used to be delivered to the hospital office where I worked, and the doughy SMELL was like a meal itself.[80]

Escaped internee Gwen Priestwood wrote:

At this time Dr. Selwyn-Clark (sic), director of Civilian Medical Services, maanaged to get us a ration of bread, and the small peice each of us received tasted – to me anyway – better than cake. (Through Japanese Barbed Wire, 1943, p. 52).

TE has to report back to his quarters by 6p.m. and can’t leave them until 7 a.m.[81] A volunteer unit is set up to deliver the bread: Owen Evans, Dr. Robert Henry and Chuck Winters (the last two were American).[82]

TE would have received a 7lbs per month personal ration of flour,[83] and his position as a baker probably meant he was rather better off than most of the other Europeans left outside the Camps; nevertheless, it’s unlikely he was free of the prevalent hunger:

Flour rations notwithstanding, the British and their fellow Europeans around town were engaged every bit as much as the internees in a constant battle to keep themselves fed. Sir Vandeleur Grayburn of the Hong Kong and Shanghai bank was reported to be looking ‘as gaunt and grey as a timber wolf’.[84]

He would also have received a rice ration, but ‘ration rice…was seldom edible. It was dust for the most part, or a kind of broken grain that Chinese had always used for pigs’.[85] Anyone who could, supplemented their rations on the black market.

January 21/22 Most of those in waterfront hotels are taken by boat to the Stanley Peninsula on the southwest of the island; until the end of the war they live here in what now becomes Stanley Camp.[86]

Feb 8 TE is interned in St Paul’s Hospital (commonly known as the French Hospital) in Causeway Bay. Also interned there is Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke, the Director of Medical Services and his family and staff, the volunteer drivers, and two other bakers: Sgm. Hammond and ‘Peacock’’.[87]

Emily Hahn records that at some point (she gives no date) many of the doctors, including Douglas and Nina Valentine, the red cross drivers, and other ‘whites’ associated with the Health Department were sent off to Stanley at short notice while the Selwyn-Clarke family were sent to the French Hospital to live. It is possible that this was also on or around February 8th.[88]

Selwyn-Clarke’s Japanese ‘boss’ has obtained the permission of the Colony’s former Governor, Sir Mark Young, to continue his work as Medical Officer for the good of everybody remaining in Hong Kong.[89] This protected Selwyn-Clarke from accusations of collaboration, which were none the less made by some,[90] including Lindsay Ride, Head of the British Army Aid Group. The same ‘permission’ probably covered TE’s work, most of which involved baking for the hospitals.

This was a time of fear and tension for the internees, as the Japanese suspected that some of those outside Stanley Camp were spying on them, so the internees feared arrest and torture by the Kempetai (roughly equivalent to the German Gestapo).[91]

At about this time the yeast ran out, so, at the request of the bakers, the Medical Department bought hops. These were used to provide a small bread ration to patients in hospitals and to the internees at Stanley. [92]

May 7 A regular flour issue is made at Stanley from this date until January 9, 1944. [93] (so presumably the bakers at the French Hospital were now baking only for the hospitals something that might have saved TE from arrest later on ).

June 29 ‘(A) hot clear day’.[94] In the morning, the Americans still in Hong Kong boarded the Asama Maru, which then sailed to Stanley and picked the Americans there in an exchange of prisoners with the Japanese.[95] In the afternoon TE married EE.[96] The best man was Owen Evans, the Matron of Honour Mrs. Almeida.[97] Owen Evan was a Friends {Quakers} Ambulance Unit Driver in China who was in Hong Kong to rest when the war broke out.[98] Tanaka was also present, and can be seen in the wedding photo.[99] The wedding took place at St. Joseph’s R. C. Church, Kennedy Rd.

It is probable after this that EE is regarded as a British citizen by the Japanese.[100] Her nationality is listed as ‘British’ on the Stanley Camp roll held at the Imperial War Museum. In any case, her after is now linked to that of TE.

August 11 A Stanley internee called Q. M. S. Stott, who had been sent to the French Hospital for treatment for an ulcer, escaped.[101]

August 18 Charles Winter writes to TE’s mother from the repatriation ship giving the family the first news of TE since the fighting began and telling them that he was due to be married. ‘During the war he did an excellent job of work in baking for practically the whole population of Hong Kong and also the Army’. He says that TE had been offered his old job at Lane Crawford’s back but hadn’t yet decided what to do. He and Lena were planning to live ‘on the compound of the French hospital’.[102]

February, 1943 From the Japanese point of view, various illegal activities are going on in Hong Kong: 1) The British Army Aid Group was organising espionage and attempting to sponsor escapes and eventual armed resistance; 2) Some internees and POWs were listening to war news on secret radios; 3) British bankers, who had been left outside Stanley to help liquidate the assets of enemy nationals, were smuggling money to the internees and POWs. 4) Dr. Selwyn-Clarke, interned in the French Hospital alongside TE and perhaps acting as his boss, was smuggling medicines, medical equipment, extra food etc. into the camps.

The Japanese came to know about all of these activities: ‘In February 1943 the Kempetai {secret police} began to strike back, with efficiency and in every direction’.[103] Bankers, including Sir Vandeleur Grayburn, the head of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, were arrested, as were agents of the BAAG.

This Kempetai action was to lead to the internment of TE and EE in Stanley Camp.

February 11, 1943 One of Selwyn-Clarke’s team, a Hong Kong citizen and voluntary social worker, Dorothy Lee, is arrested on Queen’s Rd and taken to Central Police Station. She was questioned about Selwyn-Clarke and beaten with a truncheon on her shoulders, back, knees and groin when her answers fail to satisfy the gendarmes.[104] Her initial interrogation was between 2.30 and 6 p.m. with only a twenty minute break when her interrogator went for a meal. At about 6 p.m. she was tied with her wrists behind her back and hoisted into the air; questionings and beatings continued in this position. She was then transferred to another room and beatings continued until 11.30 p. She was held overnight and given very little food. Interrogations, some with beatings, continued over the next week, and on one occasion she was beaten with a board with nails in the end. She was released on March 13. In 1947 Noma was tried for war crimes and Miss Lee’s statement was read out at the trial, she being in England. Her interrogator was named as Lishi, and other evidence named Ushiyama as an interrogator at Central Police Station. Miss Lee was arrested again on May 6 and held for questioning until May 14, but this time without mistreatment.

March 17 Arrest of Sir Vandeleur Grayburn on money smuggling charges.[105] Soon after his wife, Lady Grayburn, is either interned or enters Stanley Camp at her own request.[106] TE and EE are soon to be interned in the same bungalow.

May 2, 1943 Selwyn-Clarke arrested at French Hospital and accused of heading the British spy network: in fact his activities were entirely medical and humanitarian, although some were illegal from the Japanese point of view; it is not known if TE was involved in any of them, but this seems possible as among the items smuggled into Stanley were the containers of ‘siege biscuits’.[107] Over the following ten months Selwyn-Clarke was subjected to inhumane prison conditions and to repeated torture, but refused to implicate anybody else.[108] (He then spent another 9 months in solitary confinement, but was released into internment and survived the war.)

TE and EE were probably kept inside the French Hospital for almost a week while the Japanese searched it for evidence of espionage, and were probably sent into Stanley with 16 others on May 7, arriving at about 2 p.m.

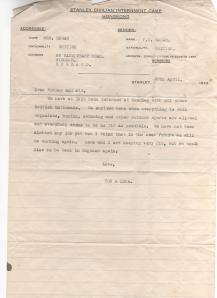

May 7-9 First letter home from TE says that he and Lena have finally been interned in Stanley Camp. The letter is dated April 30, but it was probably pre-dated to April 30 by agreement with the Japanese so another letter or card could be sent in May. His cards from Stanley carry the address Bungalow D, Room 1. Selwyn-Clarke’s wife, Hilda, and his daughter, Mary, were also interned in this bungalow (in room D6).

[3] In the possession of Brian Edgar.

[6] Les Fisher, I Will Remember, 1996, Foreword.

[9] Photo in the possession of Brian Edgar.

[12] Pre-war Letter, 2, presumably sent about the same time as the newspaper article..

[14] Chronology. TE had become involved with Freemasonry while still in theUK.

[15] In possession of Brian Edgar.

[16] Dr. Herklots in 1985 letter to Wilfred Edgar – Chronology.

[22] Wenzell Brown, Hong Kong Aftermath, 1943, 24.

[32] NTSC, 141. The defence of the Power Station by a group of men all above military age is one of the most heroic episodes in the siege ofHong Kong.

[33]UBB. The accounts of the water situation in BB and UBB are a little confusing. At some point, deliveries were necessary because a water main had been hit by shell fire (BB), but it is not clear if this was atStubbs Rd or one of the other bakeries, when it happened, and how the burst water main problem related to the absence of power after December 19.

[45] Thomas F. Ryan, 1941, Jesuits Under Fire in the Siege of Hong Kong, 1941, 168.

[48] Phyllis Harrop, Hong Kong Incident, 1943, 86-87.

[49] John Stericker, A Tear for the Dragon, 1958, 131.

[52] George Wright-Nooth, Prisoner of the Turnip Heads, 1994, 48.

[54] BB; Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke, Footprints,1975, 74

[59] BB. This is also mentioned by Fisher, 36.

[64] Banham, We Shall Suffer There, Appendix 15, ‘Kane Bush’.

[67] China Mail, October 17,1945.

[68] Jean Gittins, Stanley: Behind Barbed Wire, 1982, 33.

[69] Liam Nolan, Small Man of Nanataki, 1966, 74.

[70] Emily Hahn, China To Me, 1986 edition (originally 1944), 305.

[71] Twilight in Hong Kong, 1960, Frederick Muller, 132. Field wrongly claims that Selwyn-Clarke was interned in the French Convent.

[73] The other was Ellen Field.

[75] Philip Snow The Fall of Hong Kong, 2003,132.

[76] UBB gives January 8, but I think the published version is more reliable.

[82] BB; Gwen Dew, Prisoner of the Japs, 1943, 117.

[97] Chronology, confirmed by writing on the back of one copy of the wedding photo and the signatures of the witnesses on the wedding certificate.

[101] Banham, We Shall Suffer There, Location 1148.

[104] China Mail, Tuesday, January 7, 1947.

[105] Tony Banham, We Shall Suffer There: Hong Kong’s Defenders Imprisoned 1942-45, 2009, Kindle Edition, Location 1794.