On June 28, 1943 internees Walter Scott, William Anderson, Police Inspector Whant, Frederick Hall and Frederick Bradley were arrested by the Kempeitai.[1] On June 29 Thomas and Evelina were presented with an engraved plaque to mark their first wedding anniversary.[2]

The next day, June 30 1943, the gendarmes were out in Stanley again, continuing their investigations. Alec Summers and George Merriman, two members of MI6[3], were almost caught with their radio (they also had a gun stashed away). They managed to convince the Kempeitai that they had had a radio but threw it into the sea when the authorities announced they were forbidden. George Wright-Nooth, who was already terrified that his own involvement with radios and the smuggling of food and messages would be discovered,[4] had been in the room when the Japanese investigators came; he left speedily, even more scared. Later the ‘white faced’ pair called on him to insist that he tell the same story as them if questioned, and the three of them spent many anxious hours wondering if the explanation would be accepted.[5]

On Wednesday July 7 another four internees were arrested. There were two more men connected with the wireless: James Anderson and Douglas Waterton,[6] and another policeman, Sergeant F. Roberts. But the most surprising and worrying arrest was of senior government official John Fraser,[7] the most important man in the Camp after the Colonial Secretary, Franklin Gimson. Whatever illegal activities had been going on, Fraser knew all about them, and their perpetrators. The weeks and months to come must have tested the nerves of many people inStanley, from Franklin Gimson downwards.

George Wright-Nooth kept a diary which tells us what happened next on July 7:

The Gendarmerie were back on the rampage in camp today. All in plain clothes…

At about 1.30 pm (we) heard loud shouts in Japanese coming from the commandant’s house followed by screams. Later on Waterton came down with three Japanese and one Chinese. They were armed with spades. Waterton was made to dig a hole at the end of No 18 Block in the Indian Quarters. He was kept at it for about 2-3 hours and in the end a grey box was unearthed.[8]

At this point, another internee had a remarkable escape. A guard went to get former director of marine A. J.(‘New Moon’) Moss, who shared a room with Waterton, and had helped him bury the radio set that had just been dug up. Wright-Nooth watched anxiously as the Kempeitai pressed Moss about this, and, rather surprisingly, accepted his explanation that he’d believed he was helping Waterton secure the family silver.[9] Moss was one of the party that had planned an abortive escape, just before internment[10] – along with Gwen Priestwood, who was eventually to succeed in leaving Stanley – and, until he was certain the Kempeitai weren’t going to take him in for further questioning, he must have wished himself anywhere else but in Camp.

This incident shows something important: every arrest spread increased levels of risk and anxiety to a new group of people. Moss was drawn into the affair simply by sharing quarters with one of those involved and agreeing to do his room-mate a favour. Clifton Large, who lived with Alec Summers and knew all about the radio and the gun,[11] must have had a most anxious July. The same can be assumed about other people who, ‘innocent’ themselves knew of the ‘guilt’ of those they were living or associated with.

Internee Jean Gittins doesn’t record any illegal activity until October,[12] when she bravely took her life in her hands as part of a last desperate attempt to help those arrested in June and July, most of who were by then facing death sentences, but she was a friend of Duncan Sloss, an academic in poor health, who had accepted the role of recipient of messages from the Hong Kong resistance, the British Army Aid Group, a post that meant certain torture and death if it were ever discovered.[13] To be the friend of anyone under Kempetai arrest was in itself dangerous; in fact, to be the friend of the wife of anyone under arrest was risky – Emily Hahn was advised by one of her Japanese ‘protectors’ to stay away from Hilda Selwyn-Clarke after her husband was taken into custody.[14]

Nevertheless Sloss’s future wife, Margaret Watson, had been a close associate of the Selwyn-Clarke’s, and in early May1943 she moved into a small servants’ room in Bungalow D with Hilda and her daughter Mary. Of course, we now know that the Kempeitai only rarely arrested European women and that, amazingly, at no point during her husband’s ten months of brutal questioning was Hilda held for interrogation,[15] but this is hardly what anyone would have expected at the time, and most people were very conscious of the possibility of guilt by association: when Andrew Leiper and a colleague were eventually summoned ‘up the hill’ for interrogation about their activities before they came to Stanley those who passed by were too scared to even look at them.[16]

That was rather extreme, but after the war, the internees would have learnt the story of Norman (‘Lofty’) Lloyd at Shamshuipo, and realised that fear of terrible consequences from the actions of others was not in the slightest bit ‘paranoid’.[17]

But a surprising numbers of internees did have actions of their own to worry about. We wouldn’t know about the courageous role played by ‘Lannie’ Lanchester if her grandson John hadn’t become a writer.[18] In his memoir Family Romance Lanchester tells us that his grandmother was too upset and worried to even record the July 7 arrests and their aftermath in her diary, because she was a close friend of John Fraser, and had been helping him keep some of his papers from the Japanese. [19] These ‘papers’ were related to Japanese war crimes, and Mrs. Lanchester was one of those who could have expected a very hard time indeed if Fraser had cracked and revealed all that he knew.

We might also be getting a glimpse of John Fraser in this story from Andrew Leiper about a friend of his wife’s:

That the Japanese were on to something which had been happening received apparent corroboration from one of Helen’s friends. She told Helen that, the day before he had been arrested, one of her men friends had given her some papers and asked her to destroy them if anything happened to him.[20]

And what of mister Lanchester, the camp dentist?[21] He might reasonably have been worried for both his wife and himself – at the very least he probably knew of her ‘criminality’. And my guess is that he had another reason to worry, although his fear here would go back to early May when Dr. Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke was arrested at the French Hospital, shortly after Thomas and Evelina were sent from there into Stanley.[22]

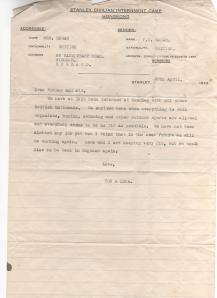

The Imperial War Museum holds a picture (reproduced in Family Romance) of Jack Lanchester and an assistant at work in Camp. Naturally, the patient is seated in a dentist’s chair. But very little was ‘natural’ in Stanley camp. The internees didn’t find a fully equipped dental surgery in the bitterly fought-over grounds of St Stephens School or in one of the outbuildings of Stanley prison. We know, in fact, that they felt a desperate need for a proper chair and that Selwyn-Clarke and two volunteers from the French Hospital went to rescue one from a pre-war government Godown that was now in the hands of the Japanese Army, nearly getting caught in the process.[23] Unless another dentists’ chair was provided later under legal, less dramatic and therefore unrecorded circumstances, the one in the picture must be the one whisked away that night, and if Selwyn-Clarke had told all he knew then the Kempeitai might well have wanted to ask if Mr. Lanchester if he knew his chair had been stolen from the Japanese army. They mighty also have had questions to ask of all those doctors who had used medical materials smuggled in toStanley by the Medical Director in the 17 months or so before his arrest.

The list of the more than ordinarily worried might well have included the Camp’s many diarists, whose records of Stanley life could have been discovered if the Gendarmes decided on a full-scale search. Les Fisher in Shamshuipo expected death if his was found, and that seems a reasonable enough assumption, irrespective of content, which could of course have made things worse.[24] And who knew which of their anti-Japanese remarks and actions had been recorded by diary-keeping friends and what the gendarmes’ response to them would be?

There was another factor that heightened the fear that pervaded Stanley camp – at all times, but most intensely during 1943. In the last days of the fighting a day or so before the Christmas surrender, word started to spread around the ‘white’ community of Japanese atrocities – of rape, torture, and the bayonetting of wounded soldiers. I’ll discuss these matters in a future post (which will focus on the internees’ fear of a final massacre by the defeated Japanese army), but it should be borne in mind that the inmates of Stanley Camp could never forget what those guarding them had done once and could never stop fearing what they might do in the future. Sometimes the constant hunger and discomfort, alongside the ever-present mutual irritations of those forced to share cramped living quarters, must have been useful in helping the internees keep their minds away from what their leader Franklin Gimson called ‘morbid thoughts’. Sometimes those thoughts must have proved unavoidable.

In another future post I’ll discuss the statistics of ‘the reign of terror’ (Emily Hahn’s half-mocking phrase) and they’ll bear out the claim[25] that the British got off lightly compared to the Chinese and that, as wartime experiences go, didn’t suffer too badly in absolute terms. But the facts and figures of what had happened by August 1945 don’t help us understand the feelings of the internees over spring and summer 1943. For the defeated in war it’s what might happen that determines emotions just as much if not more than what actually takes place, and people decide what might happen by looking backwards and sideways – they are, of course, unable to look forward to final outcomes. ‘Backwards’ in this case meant to the atrocities, some of which had occurred in the grounds of what was to become Stanley Camp, and ‘sideways’ meant to the treatment meted out to the Chinese, some of which could be heard in the sounds that came to the Camp over the walls of Stanley Prison or seen in the wretcehd parties (one of which was viewed by Andrew Leiper as he walked through the Cemetery) being taken down to Stanley Beach for execution. Put these two perspectives together….

And who, in such a situation, could feel safe? Every ‘crime’ involved others who’d helped in it, knew about it, or simply shared a room or a friendship with the ‘criminal’. If one person told all they knew, then that would lead to several others, who in turn….No-one knew where the arrests would stop or what ‘trails’ might lead to them.

There was only one more arrest that summer though. On Sunday July 11, the Commissioner of Police John Pennefather-Evans was removed from church by the Kempeitai:

Wednesday 14th July 1943 – Another sensation was caused by the arrest of the Commissioner of Police Peinefether-Evans (sic) on Sunday when he was called out of the 9 o’clock communion service and taken away. Why he has been taken away beats us, but there it is and how he is doing about a change of clothing is unknown to us as his things have not been taken away altho’ in the case of the others theirs were taken.[29]

Pennefather-Evans was one of the lucky ones. He and Inspector Whant were to reappear in camp in August. All of the others under arrest on July 7 were to be sentenced to death or to long prison terms. The executions took place on Stanley Beach, in sight of the Camp, on October 29. It was to be one of the defining days in Thomas’s life.

[1] Generally described as the Japanese Gestapo. I use ‘Kempeitai’ and ‘Gendarmes’ interchangeably. For an account of the arrests of June 28, see https://jonmarkgreville2.wordpress.com/2011/12/22/reign-of-terror-6-first-wedding-anniversary-stanley-camp/

[2] See also https://jonmarkgreville2.wordpress.com/2011/12/16/interlude-silver-wedding-celebration-in-suburbia/

[4] George Wright-Nooth, Prisoner of the Turnip Heads, 146.

[5] Wright-Nooth, 150-151.

[7] He’s called the Defence Secretary by Stericker and Gittins. Others call him the former Defence Secretary, the former Attorney-General, and the Assistant Attorney General. In 1938 he was appointed Acting Attorney General while C. G. Alabaster was in the UK – Hong Kong Telegraph, February 5, 1938, page 4.

[8] Wright-Nooth, 163.

[9] Wright-Nooth, 163.

[10] A ‘key’ written in pencil on a blank page of the School of African and Oriental Studies copy of Gwen Priestwood’s Through Japanese Barbed-Wire plausibly makes this identification.

[12] Except for buying food on the black market, and, as almost everybody did the same and the Japanese authorities were involved, this was probably safe enough.

[13] Wright-Nooth, 114.

[14] Emily Hahn, China For Me, 407-408.

[15] Hahn, 407.

[16] G. A. Leiper, A Yen For My Thoughts, 191.

[18] His novel Fragrant Harbour is a distinguished contribution to the literature of wartime Hong Kong –

[19]John Lanchester, Family Romance, 190-194.

[20] Leiper, 186.

[21] There’s a story about his work in Camp in Jean Gittins, Stanley: Behind Barbed Wire, pages 89-90. See also http://groups.yahoo.com/group/stanley_camp/message/1059

[23] Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke, Footprints, 75-76.

[24] Les Fisher, I Will Remember, 93.

[25] See Snow, 186-187.

[26] See https://jonmarkgreville2.wordpress.com/2011/12/10/the-reign-of-terror-2-fear-in-the-french-hospital/

[27] See the British Baker article at https://jonmarkgreville2.wordpress.com/2011/10/18/thomas-edgar-some-documentation/

[28] Sheridan, his fellow RASC baker, managed to escape from Hong Kong after convincing the Japanese he was Irish – http://groups.yahoo.com/group/stanley_camp/message/1194.

This story suggests the RASC men were baking in civilian clothes.

[29] George Gerrard’s Diary, available to members of the Yahoo Stanley Camp Discussion Group.