This is the American reporter Gwen Dew describing her feelings on arriving at Stanley after a relatively short time in occupied Hong Kong:

I had dreaded this minute for so many weeks that I couldn’t quite understand the feeling of release that was flooding up inside me. I was entering jail, and yet I suddenly felt freed. It was not until I had more time to analyse this that I realized its meaning: from the time I was captured, on December 23, on through the months, had been in constant contact with the Japs, my enemy; we were prisoners in a small hotel and surrounded; when the others went to camp, I was directly in the hands of the Japs, with only a few other white people free in the city of a million; I was under constant surveillance, and there was always the danger that I might be jailed, mistreated, tortured or even killed on the street, and no one would know what had happened to me. Before, I had been one lone American among thousands of enemy Japanese; now I was among friends and allies. (Dew, Prisoner of the Japs, 122)

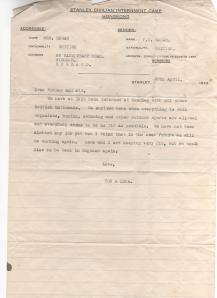

Thomas and Evelina arrived in early May and I think their initial feelings must have been very similar to those of G. A. Leiper, a banker who was sent to Stanley a month or two later. Certainly, Thomas’s first letter home is marked by the same admiration for the organisation of Stanley Camp:

(W)hen the banking contingent arrived at Stanley in the middle of 1943, we found a highly-organised community whose morale was high. We were told that, apart from a state of perpetual hunger and some anxiety regarding what might happen should the Americans or British mount a counter-attack on Hong Kong, life was at least bearable as long as one was sustained by the firm belief that liberation would come one day. (G. A. Leiper, A Yen For My Thoughts, 178)

Leiper adds that those who’d fared worse, or even died, were those who’d given up hope.

Thomas and Evelina must have been even more relieved- Leiper notes that many of the bank staff in his hostel would have been happy to be sent to Stanley in October 1942, when they expected such a move as punishment for the escape of two of their number (Leiper, 162) and, Thomas and Evelina, in the equally dangerous situation of people connected to Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke, had also probably been longing to get out of Hong Kong for many months before they were finally interned with the other enemy nationals.

For one, thing the food situation in Hong Kong was getting desperate.

At first, it had been reasonable enough, at least by the grim standards of occupied Hong Kong:

In some ways the position of these uninterned British residents was fairly tolerable. Every European…was allotted a monthly flour ration of 7lb – the same quantity as had been set aside for the privileged Indians... (Philip Snow, The Fall Of Hong Kong, 240).

But:

By the end of 1942 the food situation was dangerous; by the middle of 1943 it was desperate. People with bloated faces dragged themselves about on swollen feet, and the corpses of some 300 famine victims were found on the pavements each morning and hauled off in carts….Some of the corpses lying on the pavements had their buttocks and thighs suggestively lopped off, and rumour insisted that the meat which bubbled in the woks of the roadside hawkers might well be human flesh. (Snow, 167)

Other accounts also testify to the occurrence of cannibalism as early as 1942 (Snow, 398; Leiper, 132-133).

Leiper states that the there were more methods of supplementing rations in the bigger community than in Stanley (Leiper, 142-143); in any case, one of the main advantages – perhaps the only advantage by the spring of 1943 – of life outside Camp had all but disappeared.

No wonder that diarist George Gerrard reported that Thomas and Evelina’s group were’ glad to be in here as conditions in town are pretty hopeless’ (entry of May 8, writing about arrivals on May 7).

It’s not certain how much freedom Thomas (and Evelina after their marriage) would have had to move about Hong Kong, as this varied between different groups. He tells us that after he was moved to the French Hospital on February 8, 1942. (British Baker article, viewable at https://jonmarkgreville2.wordpress.com/2011/10/18/thomas-edgar-some-documentation/ ) he had to report back to his quarters by 6p.m. (and couldn’t leave them until 7 a.m). At first the bakers were taken to and from the Qing Loong bakery by a Japanese guard, but eventually the American-British group of volunteer drivers who were already delivering the bread to the hospitals were allowed to transport them. The same thing happened to the bankers who until July 1942 (see below) were escorted to and from work in what they called ‘the chain gang’ and were allowed very little opportunity to do anything without guards but then were allowed to march to and from work on their own and generally given greater freedom.

The bankers were sometimes able to escape Japanese control and visit friends at first, but after mid-1942 controls were tightened up (Liam Nolan, Small Man of Nanataki, 74) However, they were given ‘enemy national’ passes as a result of their good work and allowed to go to and from the bank unescorted, to shop in Central and to attend the French Hospital when in need of medical treatment (Leiper, 147-149 – however, as Leiper reports the movements of American bankers who had been repatriated by July this change might have come in June.)

All in all, there does seem to have been at least a small degree of freedom for most of those left in town. Emile Landau, of the Parisian Grill, reported seeing Charles Hyde (later to be executed) and other bankers at the grill for Sunday ‘tiffin’. (China Mail, January 8, 1947) and Emily Hahn claimed that, after the first months the Japanese relaxed their restrictions relating to enemy presence on the Peak and allowed free access to the (heavily guarded) Japanese-style tea pavilion close to the exit point of the funicular (tram).

All that is known about Thomas’s own movements is that on one occasion he was questioned by Japanese soldiers about his presence outside a place of interment; according to Evelina, they trusted his answer because he admitted at once to being English instead of claiming to be Irish. (The Irish were neutrals and so not interned.)

Leiper describes a development soon after he gained his pass in July that, if they became aware of it must have scared Thomas and Evelina: the Kempeitai began to stop foreigners they saw talking to each other on the street, separate them and ask them what they’d been talking about. If the replies were not in accordance with each other, they were taken away for further questioning (Leiper, 149).

Whatever freedom they had to move about Hong Kong was, in any case, always a mixed blessing. This is Gwen Dew’s account of the kind of thing likely to have been seen by the truck drivers who delivered Thomas’s bread in the first half of 1942:

They were free from camp – free to see two hundred Chinese die on the streets each twenty-four hours, from cholera, small-pox, dysentery, starvation, and Jap bullets.

Most of those left in occupied Hong Kong reported atrocities against the Chinese population. Soon after the Japanese victory, for example, Gordon King, the dean of the faculty of Medicine at Hong Kong University, reported seeing six Chinese looters being lined up against the wall in Ice House street and beaten to death one after the other by Japanese soldiers with heavy bamboo poles. (Snow, 86). John Stericker saw looters tied together in such a way that, when they fell from exhaustion, they strangled each other. (John Stericker, A Tear For The Dragon, 138) Even when the Chinese weren’t subject to this kind of brutality, they were the victims of mass deportations, sometimes ending in abandonment on deserted islands and lingering death.

And there was also what Hahn calls ‘one of the cruellest of the occupation nuisances’ which eventually became ‘almost unbearable’ – the institution of ‘curfew’:

(F)or their own reasons the Japanese will suddenly call a halt to all traffic in a certain part of the city. You run into a policeman who tells you to stop in your tracks, and you do. There you stand until he tells you to move again. Or perhaps, if it is that kind of day, you don’t stand: you squat. Or maybe you have to kneel. (Emily Hahn, China For Me, 381).

It’s hard to believe that the streets of Hong Kong could have given Thomas and Evelina much pleasure by the spring of 1943. But the main reason for wanting to be out ofHong Kongw as the constant danger which was the lot of anyone working with Selwyn-Clarke. (See https://jonmarkgreville2.wordpress.com/2011/12/10/the-reign-of-terror-2-fear-in-the-french-hospital/). By February 1943 the Kempeitai were arresting people they thought might be brutalised into incriminating the Medical Director, and those ‘enemy nationals’ working alongside him were obvious targets. And on May 2, when Selwyn-Clarke and two or three other health workers living at the French Hospital were finally arrested, the remaining Allied citizens began the feraful ordeal of being held prisoner there until May 7 while the Kempeitai combed the premises for evidence of spying. In the short term, being sent into Camp meant that the Gendarmes weren’t going to arrest them at that time, but there still remained the question of what Selwyn-Clarke might tell them under torture. Thomas and Evelina must have felt both relief and continuing terror as they were driven down the once familiar roads through Happy Valley onto the Stanley Peninsula.

Neither Thomas nor Evelina were great country lovers, but surely even they must have responded a little to the beauty of Stanley and allowed it to contribute to their sense of relief at being away from the dangers of Hong Kong. This is G. A. Leiper again:

…Helen and I soon settled down to our new life in the bungalow. We revelled in the fresh air, the sun shine, and the beautiful sunsets, the birds, the fresh smell of grass after rain, and the sense of freedom, even although it was limited to the camp boundaries. The feeling of belonging to a large community of ‘oor ain folk’, where the Japanese were not so much in evidence made us feel relaxed, and we realised what a nervous strain it had been living for so many months in isolation in a city where everything had become alien to us and even menacing. (Leiper, 178)

All in all, it must have been a relief to finally be sent to Stanley, however worried they were about being incriminated by Selwyn-Clarke. But less than two months later the menace had followed them and the Kempeitai were arresting people again.

Pingback: The Reign of Terror (5): The Blow Falls | The Dark World's Fire: Tom and Lena Edgar in War

Pingback: Lesley William Robert Macey | The Dark World's Fire: Tom and Lena Edgar in War

Pingback: John, Barbara and Maureen Fox | The Dark World's Fire: Tom and Lena Edgar in War