Even though neutral and apparently free, the Swiss were in fact prisoners in Hong Kong, as their representative Harry Keller found when, on June 16 1942 he wrote to the Government in Bern about the possibility of community repatriation. About 10 weeks later he received a reply to the effect that the Hong Kong expatriates might not be able to get back to their homeland because of the effects of the war in Europe, and that if they did so they would experience ‘grave disillusions’ at the lack of job opportunities. In a clear rebuke, the minister advised them to show ‘quiet and dignified courage’ and stay put.[1]

Many of the Swiss wanted to leave because the possibilities of earning a livelihood were ‘practically absent’,[2] and we know that Rudolf Zindel, a businessman in his early forties, was broke and looking for work when the job of Red Cross Delegate came his way. Later in the war his salary was 1200 Swiss Francs a month – if he was getting anything like this in June 1942 he must have rejoiced in his good luck as at that stage of the occupation it was enough to support comfortably himself and his wife and their young daughter.

But it can’t have been long before he started to wonder if he’d made a mistake taking on his new role. The Japanese put obstacle after obstacle in his way and in one important area he had to risk his own safety to do any kind of decent job.

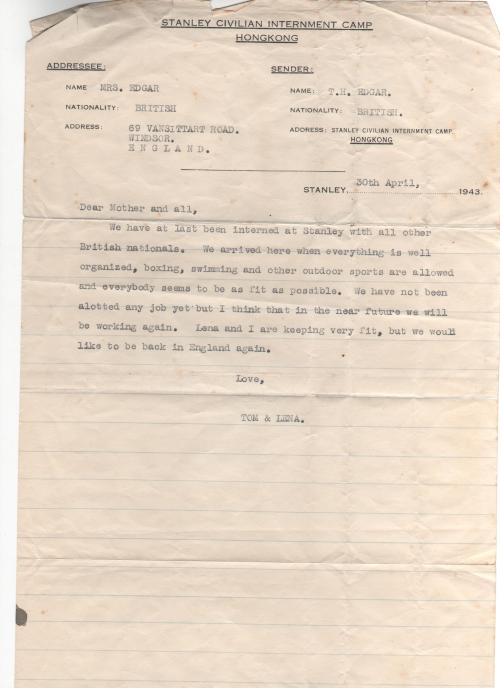

The Japanese were paranoid about the fighting men they had captured, and they provided as little information as possible about these prisoners, although in the summer of 1942 cards and sometimes even letters did begin to move slowly to and from Shamshuipo and Argyle Street Prisoner of War Camps.

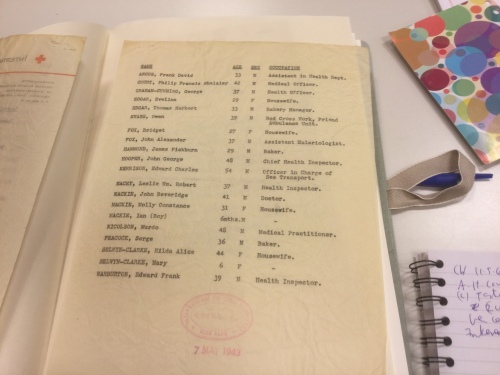

One of Zindel’s ‘greatest disappointments’ was his failure to induce the POW camp authorities to disclose information about the whereabouts and welfare of the Hong Kong POWs. His requests were batted away and he was sent on a wild goose chase of fruitless enquiries;[3] a personal appeal to Prince Tatsugu Shimadzu, head of the Japanese Red Cross failed, so he was reduced to indirect means of gathering information.

Most of these were legal – he could, for example, learn a lot from the receipts for the 10,000 remittances sent through his office to the Prisoners of War. But if one of these receipts was marked ‘undeliverable’ that left him with three possibilities: 1) the man was dead 2) he was in Gendarme custody 3) he’d been sent to Japan as a labourer.[4]

This meant that he was in no position to reply to enquiries, so he adopted a courageous expedient: he bribed a Japanese officer attached to POW headquarters with occasional presents (a Swiss watch, razor blades, a civilian suit….). Once or twice a month he slipped into his hands a small folded piece of paper which contained the names of those whose fate he was anxious to ascertain. On the next visit, the officer would secretly return the list to Zindel with coded signs signifying the prisoner’s state: dead, alive in camp, transferred to Japan, or ‘unknown’. This system enabled him to reply to a large number of queries, but had to be abandoned when the Gendarmerie placed their own man in Prisoner of War Headquarters.[5]

Zindel calls this course of action ‘dangerous’ and this is no exaggeration. Bribing a Japanese officer to become a spy – which is how the authorities would have seen the matter- would almost certainly have meant a most unpleasant interrogation with a likely sentence of death to follow. In fact, two of his fellow Red Cross workers – delegates whose position the Japanese never recognised – were executed in Borneo on charges that included seeking information about POWs, with no bribing of a Japanese officer involved.[6] That was in Borneo, in May 1943 when Zindel faced arrest himself.

He’d been warned in February that his Kempeitai dossier was getting thicker and as part of the crack-down that began that month he’d been followed by two men and had his phone tapped; even a few of the people he helped denounced him to the Japanese! Some of these ‘needy’ aid recipients were almost certainly agents provocateurs sent to try to get him to carry out illegal relief – the Japanese had told him they didn’t want him involved in relieving Asians, who would be looked after as part of their Great East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere. Nevertheless, in some cases, he did provide ‘illegal’ relief to Eurasians.

He was also told he was suspected of espionage in Stanley. In May, at the time of the mass arrests designed to break up the (non-existent) spy ring the Japanese believed had been run by Dr. Selwyn-Clarke, who Zindel had always worked in loose co-operation with, he was warned he would be dealt with if he went wrong just once more. He decided to act pre-emptively and appeal to a senior Japanese of his acquaintance, a tactic that worked and which he used again in the autumn when he was once more being harassed by the Kempeitai: this time he appealed to the head of that organisation, the much-dreaded Colonel Noma, who proved to have a detailed knowledge of the Red Cross and its problems, something that must have been both re-assuring and disturbing. In any case, Noma seems to have called off the pursuit.[7]

So when, during the sticky Hong Kong summer of 1944, Zindel faced a difficult decision he was no stranger to illegal activity and the dangers it posed.

His problem was this: Hong Kong’s official currency, the Military Yen, experienced more or less continual depreciation during the occupation and things were reaching a crisis point. Most of his relief work was paid for by remittances from the British, Canadian and American Governments, sent to the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva, and transferred to Hong Kong via Tokyo, where the Japanese changed the sum, received in Swiss Francs, into Military Yen at the official rate of about one franc to one MY. By summer 1944 this amount in depreciated Hong Kong currency wasn’t enough to enable him to buy the supplies he needed for his work, which by that time was based on housing and feeding most of the dependents in Rosary Hill Red Cross Home and sending food, medicine and money into Stanley. In fact, Zindel was obviously soon going to find it hard to feed himself and his family on his Red Cross salary. As far as I can reconstruct his situation, he was faced with three basic choices.

The safest course of action was simply to resign as Red Cross delegate. We know that at some point – maybe in summer 1944, maybe earlier – he did indeed approach the Japanese to tell them he was standing down. They loved the idea but wouldn’t accept anyone in his place, and he felt that to resign, under such circumstances, would have been a betrayal of trust. He could do little but that little was better than nothing.[8] Of course, if he’d left the Red Cross at any point he would have lost his SF1200 a month salary, but, like other of his co-nationals, he could have drawn on loans from the Swiss Relief Fund and, in summer 1944, it would be a reasonable calculation that he, Alice and Irene would make it through to the end of the war. And in such circumstances he would have been as safe from the Kempeitai as any European in occupied Hong Kong could be.

The second plan, reasonably safe and assuring Zindel a continued income, would have been to carry on with his Red Cross work doing the best he could with the limited purchasing power at his disposal. He could, for example, have sent the Stanley internees cash only and not tried to send in health-preserving foods and life-saving medicines, while shutting down Rosary Hill and forcing the dependents to revert to the system of small cash allowances at levels that would have meant the speedy demise of those with no other source of income or sustenance. He would have had lived with the knowledge that he was doing little to preserve life, but this would not have been the fault of the Red Cross, and such a course of action would not have added to the risk of arrest he was running simply by trying to help the British and Americans.

Rudolf Zindel – who had already risked his life and had come close to arrest on at least two occasions in 1943 – rejected both these plans and instead chose a third course, one that put him in huge personal danger.

To understand what he did we need to consider another aspect of the financial situation in the second half of 1944. Not only were Military Yen plunged in value -with further falls likely – those who had large holdings of them were worried that when the British returned (as they probably would) the Japanese currency would immediately be declared invalid, leaving their holdings literally worthless. (The British did in fact try to do this, but soon back-tracked because of the problems this caused.) This fear meant there were wealthy people who, in return for a reliable promise of repayment in a solid currency after the war, were willing to advance loans in Military Yen at much better rates than the official 1=1. In fact, Zindel managed to get MY21 for each Swiss Franc he committed in return:

In raising money locally, I contravened Japanese regulations and thereby exposed myself to a considerable risk.

He asked the Red Cross to pay his salary to relatives in Switzerland so that could act as collateral.[9] But that wasn’t enough to finance the entire relief operation he was responsible for:

(F)or this reason, {the possibility of being caught in illegal activity} and so as not to compromise your committee{the I.C. R.C} I raised the money in my own name, using as backing…personal resources I had in Switzerland and the U.S.A.

This added the risk of financial ruin to those of being imprisoned, tortured and executed by the Japanese for breach of their currency regulations.

This procedure involved the risk that, under certain circumstances, I, or my heirs, might not be able to recover from your Committee the commitments entered into by me personally for the benefit of the British, American and Delegation interests….

The last remittance Zindel received through Tokyo was in April 1945[10] – after that the chaos and destruction of the final stages of the war prevented any further payments. Zindel carried on, now supporting the relief effort entirely from his own pledged resources. In that time he spent over 3,000,000 yen.[11] Of course, he hoped the Red Cross (and the Governments which paid it to help their citizens) would re-imburse him after the war, but he had no way of being certain this would happen.

During this period when he was regularly breaching Japanese exchange regulations, Zindel defied their rules on at least one other occasion, bringing further possibility of retribution, but saving five lives.

That was the number of diabetics in Stanley, and they needed 2,400 units of insulin a month, provided mainly by the Red Cross. When during the summer of 1944 it became known the camp would be taken over by the Japanese military, he sent in as much as he could lay his hands on as he realised it might be difficult to do so later. He then had discussions with the new administration which told him to suspend supplies as they would furnish the insulin themselves. He was unhappy, but his visits had been reduced to one every six months and he was no longer permitted to speak to the internees or Gimson, so he couldn’t check the situation.[12]

In spring 1945 Zindel received ‘an underground chit’, presumably from Stanley, which showed him the Japanese had failed to supply the promised insulin. Although he realised he’d have a problem explaining his actions, he immediately purchased a few months’ supply and got permission to send it into camp. After the war, Gimson told him the Japanese had made enquiries as to how the ‘leakage’ from the camp occurred but had accepted the story that individual internees had mentioned the insulin problem in postcards to friends in town and one of these had got past the censor. Zindel felt that the incident showed the Japanese had no compunction about letting the diabetics die, even though the insulin came at no cost to them, and that action by him solely on the strength of unofficial information put at risk both the Delegation and the internees.[13] This suggests that he didn’t act on such ‘unofficial’ messages very often.

Nevertheless, as the war came to an end, Zindel was told he was on a list of eleven Europeans about to be arrested – the third time he had been close to the nightmare dreaded by everyone in occupied Hong Kong.

Zindel refers to the arrival of Harcourt’s fleet on August 30, 1945 and the return of British administration as ‘our liberation’ – with no pretence of neutrality. Like many others, he suffered as a result of his experiences during the occupation, but he agreed to stay on at his post in order to provide relief for the now imprisoned Japanese. At the same time, he had to waste his energy fighting the lies about the Red Cross and his own personal role that were circulating in Hong Kong:

(U)nfortunately, my sustained efforts during the 31/2 years of Japanese Occupation (in the face of unceasing difficulties, set backs and frustration as well as occasional threats to my personal safety, had sapped my vitality to an alarming extent, and my expectations that I would pick up quickly with the better food and the less strenuous conditions after our Liberation, have only been partly realized… I am therefore carrying on my work under a considerable handicap and I am keenly looking forward to my forthcoming holiday in Switzerland, which will represent the first break during 9 years in the Tropics.[14]

I’ll detail British Hong Kong’s appalling reaction to Zindel’s work in more detail in a future post. For now, let the judgement of Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke – who usually adopts the generous policy of not mentioning anyone who he can’t praise and at least has the decency to leave out Zindel’s name – be itself judged against the record I have described:

A year after the capture of Hong Kong the International Red Cross was allowed to send a Swiss representative {Zindel wasn’t sent, he was already in Hong Kong and, as I showed in this post, he was hard at work from late June 1942} and to him I handed over most of my welfare duties. Although I was glad to do so, I gained the impression that he had heard rather too much about Japanese severity to act with the necessary boldness on behalf of the prisoners and internees. And from what I was told after the end of the war my foreboding had been justified.[15]

Castle at Sargans, Zindel’s birthplace (Wikipedia – Adrian Michael, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sargans)

Note: Most of these references are given in incomplete form to prevent plagiarism.

[1] Letter from the Swiss Minister, sent via Camille Gorgé on August 18, 1942 to Keller, pp. 1-3 (Swiss Federal Archives).

[2] Letter from Keller to Hoffmeister, 30 July, 1942 (Swiss Federal Archives).

[3] Rudolph Zindel, ‘Supplementary Report – A Few Aspects of the Delegation Work in Hong Kong Under The Japanese Occupation’ pp. 3-4 in BG17 07 074 (Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross).

[4] Supplementary Report, 11.

[5] Supplementary Report, 12.

[6] Charles Roland, Long Night’s Journey Into Day, Kindle Edition, Location 4689.

[7] In Correspondance Avec M. Zindel á Coire et Shanghai, 25.05.46-12.10.46 (AICRC).

[8] Russell Clark, An End to Tears, 1946, 67.

[9] General Letter no. 29/46, 28 March 1946 pp. 1-2, in Lettres recues (General Letter) 02.01.46-05.05.47 BG017 07-074 (AICRC).

[10] AICRC.

[11] Clark, Tears, 66.

[12] Supplementary Report, 12.

[13] Supplementary Report, 13.

[14] General Letter No. 21/46, 20 February 1946 p. 2 (AICRC).

[15] Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke, Footprints, 1975, 71.

Lake Geneva, Montreux

Lake Geneva, Montreux Bern

Bern