At the end of June I attended a conference at Rome Sapienza. The theme was ‘postmemory’ – in my case, that means my relationship to my parents’ experience of the war and the strange way in which their memories intermingled with my own.

Below is a slightly revised text of the talk. PP refers to Power Point slides, which I’m afraid the reader will have to imagine, and Word Press has taken out the footnotes as usual.

In the Dark World’s Fire: a personal-theoretical investigation of postmemory of the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong

PP Empire of the Sun

There’s a scene in Steven Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun.

PP Cadillac of the Skies

Jim, a boy prisoner based on James Ballard the author of the original novel, runs outside during a raid on the airfield next to his internment camp shouting a phrase he’s learnt from one of his American ‘protectors’, ‘P51, Cadillac of the skies’. It’s a scene Spielberg himself regarded as central, and it wasn’t the first time the film had brought me to tears, but now I became aware of something strange.

I was crying because of the resonance with my parents’ time as civilian internees in Hong Kong’s Stanley Camp and I realised that I was experiencing their experience with something stronger than empathy. In a way I couldn’t understand, those experiences felt mine as well as theirs and the tears seemed more powerful and more personal than any I’d cried during a catharsis-based psychotherapy in the early 1980s. Many years later this ‘confusion’ went still further. Another Spielberg film, War Horse, led to crying about a time in my life when I perceived myself as the object of a lot of hatred. But soon I apparently found myself crying my father’s tears at the hatred coming from the Japanese occupiers.

How had such a strange transfer come about? Is it evidence for Cathy Caruth’s claim that trauma is by its nature belated, and that it’s only in future generations that experiencing can take place?

The Japanese attacked Hong Kong on December 8th, 1941 and my father was in charge of the Colony’s bakeries during the eighteen days of resistance. About a month after the Christmas Day surrender most British civilians were packed off to Stanley Internment Camp on a southern peninsula of the island.

PP Stanley

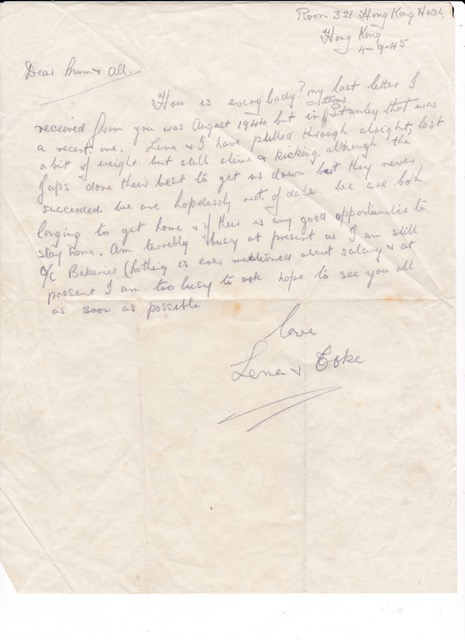

But Thomas volunteered to stay uninterned, living in the occupied city, to bake bread for the hospitals, and in January 1942 he met my mother, Evelina, a Eurasian with a neutral Portuguese passport. They married in June:

PP Wedding photo

That’s Lieutenant Tanaka, a humane Japanese officer who befriended my parents. In May 1943, after the arrest of my father’s boss on spying charges, they were sent off to join the others in Stanley Camp, where they passed the rest of the war.

It’s crucial that this was very different from an experience of the Holocaust. So much so that the death rate in Stanley Camp was comparable to peace time.

Now, ‘trauma’ is a tricky concept, but what’s common to most definitions is the idea of an experience so unpleasant and overwhelming that it defies immediate processing and leads to memory traces that make themselves felt later. My parents’ time in occupied Hong Kong was full of ongoing humiliations and deprivations. Stanley was massively over-crowded, the food was always inadequate and sometimes the rice came with weevils and mouse droppings. There were also the kind of high impact traumas focus on which has given rise to the Bessel van Kolk and Cathy Caruth theorisation of events so overwhelming that they shut off ordinary consciousness and representation and leave an imprint of the experience burnt into the brain. A typical example of that kind of trauma: my father’s journey in quest of baking supplies, speeding through shells and shrapnel with a terrified and incompetent driver. A couple of years into the occupation he was involved in an attempt to keep a woman inside the billet so she wouldn’t see her husband being beheaded for resistance work on the beach below.

PP Hyde

But worse than anything that happened – and a further complication of the concept ‘trauma’- was the fear of what might happen. In June 1942 my father played a role in the escape of a British soldier. To be interrogated about that would have been an unimaginable experience that he must have spent a lot of time imagining.

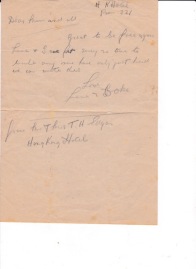

My mother had her own mental terrors. This passport photo is one of the few objects that survived internment:

PP passport photo

I think she must have kept her Portuguese credentials close during the period of mass rapes, mainly of Chinese women, that followed the British surrender.

Deprivation, high impact trauma, and terror about what might happen. Nevertheless, they both loved Hong Kong, and even wartime had some positive elements. In many ways activities and personal relations in Stanley Camp were more fulfilling than in pre-war society, and beneath the torpor there were new challenges and a sense that you might at any moment need all your human capacities in order to maximise chances of survival. There’s a certain nostalgia about some of the writings about Stanley that, again, takes us completely outside the world of the Holocaust, and indeed the death railway in Thailand and even other Japanese camps for civilians – significantly Ballard’s Lunghua was also one of the milder camps.

So what emerged in my parents was a complex form of memory in constant engagement with the conditions of their postwar life. They certainly didn’t seek to avoid wartime associations. When I was born in 1950 they were renting a flat next to a notorious Japanese torture chamber. Back in the UK, in 1955 my father designed a bungalow that echoed their billet in Stanley Camp, down to the parquet floor. The conscious stage of my formation of postmemory began in a house that acted as a mnemonic of the Hong Kong war.

PP Bungalow

The Kindness of Women, Ballard’s sequel to Empire of the Sun, makes it clear that in the greyness, literal and symbolic, of English life he came to long for the far eastern light of Shanghai and Lunghua, even to the extent of fantasising a return to the conditions of war through an atomic explosion. My parents remembered the traumas of the occupation in the way they did partly because in all the ennui and limitations of the 1950s they were nostalgic about a time that challenged every faculty just to survive. In the isolation of a nuclear family they were haunted by the camp’s communal living, even when that came as a bunk bed on the floor of a lounge shared with a couple they didn’t like.

I knew my parents yearned for Hong Kong and in some ways for the life of internment so that acquired a powerful glamour for me. My mother had a music box and the tune it played I came to associate with Stanley. I learnt to turn the constant electrical hum in the air into that music, always playing somewhere above my left ear. I was, of course, seeking my own forms of escape from the greyness.

I’ve begun with that nostalgia, which was probably specific to a small percentage of settings, because of its importance in the most conscious parts of my postmemory. Although the terror, deprivation and horror experienced by British civilians in Hong Kong was not on the scale of other places it was more than enough to dominate post-war memory. I want to examine this through trying to answer the question:

How did their memory become my postmemory? How did that terror and horror come through to me?

Like most of those who went through the occupation my parents decided not to speak much about it so as not to burden their children. But sometimes, in my father’s case, things forced their way out. And it was the worst horrors he felt compelled to talk about – contrary to the idea that trauma resists linguistic representation. He told me about being with Mrs Hyde while her husband was executed on the beach below, alongside at least one other man he knew personally. He spoke about the way the Japanese forced the Chinese into junks and sunk them in the harbour for artillery practice. Always when he talked about this violence there was an underlying anger. It covered over his fear and it was directed both at the Japanese and at me, for not being able to understand. The only time he spoke in a different register was when he mentioned Captain Tanaka.

That was verbal transmission. Eva Hoffman tells us that the first transmission to her was not memories expressed in words, but ‘something closer to enactment of experience… the past broke through in the sounds of nightmares, the idiom of sighs and illness, of tears and (the) acute aches…’.

I was a fearful baby who sometimes wouldn’t sleep on his own, so I find that invocation of nightmares particularly resonant. A key moment in my own understanding of the ‘idiom of illness’ came in about 1960 when I was 10. My mother had a nervous breakdown in which she spent most days lying on the sofa, stricken with headaches and suicidal thoughts. It was seen by the doctors and neurologists as a reaction to the menopause, which was of course part of the truth. But the real content of the experience – the terror of the war – was signalled clearly enough: her years of travail began the day she sat down and couldn’t stop her knees from trembling and it ended the day she sat down and her legs remained still.

Between 1968 and 1972 I recreated their ordeal in occupied Hong Kong by building my own prison – obsessive reading for almost every waking hour which went on in its extreme form for almost exactly the duration of the occupation, three years and eight months. This was in some ways functional for someone doing a literature degree but the main purpose was to minimise the pressures of life in the late 1960s as I was unable to deal with them. After the degree, I escaped from my own prison through a nervous breakdown modelled on my mother’s, and actually found myself consulting one of the same neurologists.

I’ve described my creation of the music of Stanley and later breakdown as if they were free choices, and as an Existentialist of an extremely heretical kind I’m interested in the way some theorisations of trauma challenge the fundamental tenet of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness: no experience is so overwhelming as to deprive human consciousness of its freedom to choose its response.

There’s an early but classic critique of Sartre’s theory of freedom by the American philosopher Vivian McGill which praises him for resisting, amongst other things, the use of trauma as cop out – he mentions Otto Rank’s idea that the personality is formed in large part by birth trauma. But McGill goes on to suggest that choices are inevitably made on the basis of our ‘psychobiological nature. Of course, Sartre denies that there’s any such thing as ‘human nature’, but both theory and my own experience put me with McGill on this issue.

I want to try to square the circle and suggest that both the original memory and the subsequent postmemory are created in a dialectic between freedom and determinism.

This is no simple dichotomy in which verbal communications leave consciousness existentially free and the kind of bodily-energetic-emotional messages described by Eva Hoffman compel a particular response. Nevertheless that type of transmission begins much earlier – my own experience suggests it begins in the womb, but in any case body messages begin at a time when the psyche is more open and more vulnerable and they don’t stop when the stories start.

It’s in this bodily-emotional-energetic transmission that I find the most obvious limits of freedom. Sartre denies the existence of such a thing as human nature, but I believe that human subjectivity is pre-formed by evolution and one thing I’ve found about mine is that I react to the most powerful elements in my consciousness and some experiences are so powerful they leave little choice as to the form of reaction. An example. Sometimes, for no apparent reason, I’m filled with terror which, traced back, always has its origins in Japanese Hong Kong, although of course with way stations in my own life. Very early on my parents’ continuing terror forced its way into my consciousness. But at the same point at which choice was rendered impossible, freedom began. Introspection suggests that the terror is the liveliest state of my bodymind in the circumstances in which it occurs and for that reason I give consent to its reappearance, just as in the early 1970s I gave consent to various elements of unhappiness and turned them into a ‘nervous breakdown’.

So, contrary to much theorising, there are no repetitions, re-enactments or literal returns in the memory or the postmemory of trauma, only recreations, old feelings put to work in new situations in a way that can be called neither free nor determined, or both at the same time.

In spite of all I’ve said, I do not believe that I experience my parents’ experience, that their belated traumas find their witness in my tears.

PP Stanley 1996

When I first stood in what once had been Stanley Civilian Internment Camp, a stunning location looking out over the South China Sea, I was overwhelmed with the thought that, amidst all this beauty, even if there had been nothing bad in my life except the reflection of the pain caused in this place, I would have been destroyed.

It was a comforting thought because it made so much clear, including the difference between my parents’ experience and my own. When I took on some of their memory, whether voluntarily or through being overwhelmed, it was in both cases knowing, crucially knowing, it was theirs not mine. Those tears while watching Empire of the Sun were of confusion not identification and even when I apparently cried my father’s tears at the dark world’s fire of hatred in Japanese Hong Kong I never lost the knowledge that they were his and that he had experienced the occupation not me. That’s why I could cry them.

As Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer so rightly suggest in their foundational text, we must resist the equation of memory and postmemory, especially when it comes marked with the specious authenticity of tears.