I sometimes fancy trying my hand as a writer of popular romance. A short novel perhaps, or better still a film script. How about this for a scenario: Time: the ever-popular background of the Second World War. Place: the exotic and beautiful British colony (as it then was) of Hong Kong. Action: the sirens whine, the shells whistle and crump, the fires blaze, and amid scenes of great confusion and horror the gallant defenders are overcome.

While most British civilians are suffering the fears and indignities of the defeated, a few are lucky enough to find themselves in the hands of a compassionate Japanese Army officer. He sets the bakers among them back to work, re-opening a small Chinese bakery to make bread for the hospitals. Everyone’s hungry and the Colony’s European population is desperate for the taste of bread; word soon gets round, and queues form – people will pay anything for a precious loaf. The bakers know that they’ll be packed off somewhere much worse if they abuse their position, but one of them refuses to let his friends leave empty-handed and gives them bread for free. While his comrades are remonstrating about the danger he’s putting them all in, a friend steps forward, asking for supplies not just for himself but also for his tenant, a pretty young Eurasian woman….

Everyone in Hong Kong’s been at risk of sudden death from shell or bomb during the fighting, and they all know that nothing can be taken for granted in the brutal new order that’s emerging. Things move fast, and the baker and the young woman are soon romantically involved.

Let’s make them an unlikely couple too, the kind who would never have got together in normal circumstances, but are thrown unexpectedly into each other’s arms by the heightened emotions of war. He’s working class and as English as they come – Hampshire and Berks – while she’s from a good Macau family and has lived all her life in the south China world.

Their romancing takes place to the backdrop of Japanese soldiers patrolling the streets, tearing down the old English signs and erecting new ones, this time in the languages of the East, while all over the former Colony the message ‘Asia for the Asiatics’ is being drummed into a population that seems terrified at the atrocities going on all around rather than over-joyed at their liberation from British rule. All this might lead up to a big scene in which the woman is offered the chance of returning to the safety and comfort of her neutral homeland (let’s give her some well-off friends to underline how much she’s sacrificing) but chooses to stay with her man, braving discomfort, slow starvation and the possibility of violent death at any moment.

Skip a few months and zoom into the couple marrying in church, and then standing on the steps for the group photo – the camera picks out a man in a Japanese officer’s uniform – what’s he doing there? – and then follows the couple as they walk off hand in hand, still prisoners but now at least together.

There follow three more years of terror and deprivation. Our hero and heroine, alongside the whole Allied community, are once again staring death in the face – either from starvation or massacre, but they’re saved by the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, one of the most terrible events in human history. They stumble out of their prison camp, play their part in the building up of a new world, and manage to hold a difficult relationship together all the way through to the husband’s death bed.

I know, I know these days everyone – romance readers and cinema audiences alike- demand something a bit more sophisticated than that. Why, the plot’s nothing more than a bunch of old-fashioned romantic clichés, stereotyped situations, exaggerated dilemmas and unlikely outcomes.

But that, in sober fact, was the life together of Thomas Herbert Edgar and Evelina Marques d’Oliveira.

They would not have given each other a second thought before the war. They came from such different backgrounds and lived in such different worlds.

Although things were getting more liberal in Hong Kong in the three years before the war, many of the British held on to a mythical view of racial hierarchy which meant that they and the other ‘Europeans’ were at the top of the heap and the Chinese at the bottom – in accord with this pernicious logic, Eurasians, who at least had some ‘white’ blood, were somewhere in between,[1] but probably closer to the Chinese: the Europeans had their own schools, for example, and so did the Eurasians, but those who didn’t have a place were generally educated alongside Chinese.[2] In fact:

Eurasians in a European social gathering created a climate of unease and psychological tension…Even highly educated Europeans reacted strongly against mixed marriages.[3]

Not surprising that there wasn’t much socialising between ‘whites’ and Eurasians.[4]

After their victory, the Japanese published a newspaper the Hong Kong News – a lying propaganda sheet, but one that sometimes told the truth:

(The) Eurasian when he seeks employment is classified as a ‘native’ and is required to accept ‘native’ pay.[5]

Evelina knew this for herself: she’d come to Hong Kong to work, something that as a middle class woman she was not expected to do back home in Macao, and before the war she had various jobs in sales. Eventually she rebelled and asked her latest boss to pay her the same rates as the European staff – to his credit, he agreed, but it didn’t change the system.

But race wasn’t the only prejudice in pre-war Hong Kong. There was a strict class hierarchy too, with the bankers and senior government officials at the top, wealthy businessmen not far distant, and everyone else graded according to job, salary, location, accent and so on. From this point of view, Thomas was really little more than a jumped up manual worker. True, he managed the bakery for Lane, Crawford, the most prestigious Department Store in Hong Kong, but he was a hands-on baker, someone who didn’t just tell others what to do but had learnt through a tough apprenticeship to do it all himself. And anyone who cared to enquire about his family would have learnt that he was the son of a domestic servant, later a would-be theatrical landlady, and a soldier-turned-driver. This is a photo of Thomas’s mother with her six children:

Evelina Marques d’Oliveira, on the other hand, came from a distinguished Macanese family. Her grandfather was a judge in Lourenco Marques, and there’s still a street named after him in Macao. Her father, Antonio, was a tea merchant, who took a Chinese wife; she died of TB when Evelina was three, and he later remarried.

Evelina’s best friends in Macao had been three Eurasian sisters, the Leitaos, daughters of a leading lawyer. When her father moved to Foochow (Fuzhou), a centre of the tea trade on the south China coast, she was sent back to Macao to be educated privately, probably at the elite Santa Rosa de Lima school. She spoke English and Portuguese fluently, and at some point was to become reasonably proficient in two forms of Chinese. She also acquired secretarial skills, and in many ways her written English was better than Thomas’s.

Thomas had been educated at the local state school and, although a bright boy, had to leave behind his studies and help his family’s finances by getting a job. At first he’d been a clerk in a motor company, but in 1927 – after his dreams of a boxing career ended with a knock-out – he began a three year apprenticeship at a baker’s, which meant long, unsocial hours, full of sweat and physical labour, at first working unpaid to learn his trade.

They had opposing religious beliefs too: Evelina was a Catholic, while Thomas was an enthusiastic Freemason, and therefore regarded as an enemy by the Church, a feeling which he reciprocated.

Thomas on a day out at Mt. Parker in February 1940

Perhaps one thing symbolises most clearly the difference between the two worlds they’d been brought up in. The terraced house close to the river and in the flooding zone, which was all Thomas’s family could afford, was already full with him and his five brothers and sisters, but his parents still found room to cram in paying customers, actors appearing at the nearby Theatre Royal. In contrast, Evelina’s family bought a young girl as a servant under the old mui-tsai system – ‘We treated her well’, she said, many years later. This could have been true; British radicals in Hong Kong hated mui-tsai as a form of slavery, and there were indeed hideous abuses, but in many homes they were treated as part of the family – which didn’t necessarily spare them from long hours of work under a harsh discipline, of course.

You could say that Thomas and Evelina were united only by their relative disadvantages in class-conscious, race-obsessed Hong Kong. And perhaps by one other thing. Evelina was 28 when they met, 29 by the time they married. She’d had boyfriends: perhaps Horacio was one of them…

…but she was leaving it rather late to get married according to the ideas of the time. Thomas had been very shy when he was a boy; he sometimes used to cross the road to avoid walking too close to another person, although he’d probably got over that by the time he went to Hong Kong. Nothing is known about his relationships there though. In any case, when his family heard the news of his marriage they were pleased for two reasons: firstly, it meant that he wouldn’t get himself killed trying to escape, and secondly that Thomas had found a woman who was willing to marry him in spite of his heavy drinking! Before the war he and two friends had been nicknamed ‘the three terrors of Hong Kong’ because of their alcohol-fuelled exploits.

When the Japanese attacked on December 8, 1941 they were again in very different situations: Evelina’s Portuguese passport meant that she was a neutral, although no-one knew how far the Japanese would respect this. About Thomas though there was no doubt: he was an enemy and, as he was also young (28) and fit, he would be expected to play his part in the British defence.

Most able-bodied young British men had to join the Hong Kong Volunteers, a home guard with a dilettante reputation but which surprised most people by fighting with courage and distinction when the time came, but in October or November, 1938 as the Japanese war with China moved close to the Hong Kong border, Thomas received a letter telling him not to get involved in military training but to concentrate on preparing his bakery for any ‘emergency’. This was the new Lane, Crawford Bakery in Stubbs Rd, opened that year, and hailed in company adverts as the most hygienic in the Far East – disease was another Hong Kong obsession, this one with more reason.

So, almost exactly three years later, when the attack did come (December 8, 1941) Thomas was ready. The first air raid began at about 8a.m., and by that time he’d probably already left his lodgings in Broadwood Road and taken command in the Bakery. He was immediately promoted to Deputy Supply Officer Bakeries, which meant that he was in charge of most of the bakeries in Hong Kong, and he decided to start off by producing all the bread the population needed using the Lane Crawford machinery. If Stubbs Road became too dangerous, he’d prepared for production at some smaller premises in Wanchai, hoping that one or more of them would still be viable.

After the fall of the mainland on December 13 the bakery itself was in the line of fire between the Japanese and British forces. Thomas slept in the office chair, until the staff were given some camp beds. On December 19, the army field bakery in Deep Water Bay was forced to stop work, and Thomas’s responsibilities increased, as he now had to try to make sure that those doing the actual fighting had bread. Those who took the loaves from the bakery to the supply points were very brave men and women indeed. Hong Kong was being constantly shelled and bombed, and, although the Japanese made some effort to avoid civilian areas, there were many casualties. They also knew that the Japanese were not always taking prisoners.There was no water from an early stage of the fighting, so special deliveries had to be made by the Fire Brigade. Eventually there was no electricity either. In spite of everything, the bread went out, as ordered.

As the Japanese moved inexorably westwards from North Point towards the Hong Kong heartland of Victoria, the bakery’s situation became untenable. When it did, on December 21, Thomas moved production to some of the smaller bakeries he’d prepared for the task. These must have been terrifying but exhilarating days for him. He could die or be painfully wounded at any moment, but at the same time he was doing his duty, no matter what, moving around, working frenetically to coax the last ounce of production out of small and old-fashioned bakeries.

Thomas, helped by RASC bakers who arrved on the 23rd after an eventful journey from the south of the island, kept the bread supply coming until December 25 – later known in Hong Kong as Black Christmas – when the defenders were forced to abandon their hopeless resistance. Like the other Lane, Crawford employees Thomas was told to report to the company headquarters at Exchange House in Victoria’s Des Voeux Road, which was to become his first place of internment. He spent Christmas evening pouring away the alcohol stocked by the company’s restaurant- everybody feared what was about to happen, and it would have been foolish to leave around anything that could inflame the conquerors further.

The next morning Thomas woke up to meet the new rulers of Hong Kong for the first time. He was soon to realise that he was lucky: Exchange House was under the control of a communications officer, Captain Tanaka, a fine man whose generosity has been recorded by other former prisoners. Tanaka allowed him to go to his lodgings to get a new shirt – he’d used the one he’d been wearing to bind the wounded, and it was bitterly cold by now. In the days to come, Tanaka gave good food to the internees, and even arranged film shows for them.

On January 5 most of the Allied civilians were assembled in squalid waterfront hotels and from there they were soon to be sent off to a large improvised place of internment on the southern peninsula – Stanley Camp. Captain Tanaka arranged for Thomas and his fellow bakers to stay in Exchange House and on January 9 he gave them permission to go back to work to help feed the many patients in Hong Kong’s hospitals.

Evelina had a neutral’s passport, but as a Eurasian woman she must have been terrified as the Japanese troops took over. Everyone had in their minds the possibility of mass rape and murder, as had happened after the fall of Nanking. Years later in England she’d speak about her fear of the bombs, and sometimes hide in an understairs cupboard during storms if the thunder got too loud. But there was another, more immediate problem: hunger. Food was hard to come by during those chaotic, panic-stricken days. Luckily Evelina’s landlord (probably Robert Bauder, a Swiss national who like Thomas worked for Lane, Crawford) knew someone who could probably get her something to eat….Some time in January 1942 he took her to the Ching Loong bakery in Queen’ Road, where Thomas and his colleagues were at work, and the relationship began.

On February 8 Thomas was transferred to internment in St. Paul’s Hospital, generally known as the French Hospital, in Causeway Bay, but he continued to bake bread – and to see Evelina. The team of drivers who delivered this bread included an American, Charles Winter, and a Welshman Owen Evans, a man who was unlucky to have been there at all. He was a driver with the Friends Ambulance Unit based in southern China who’d been sent to Hong Kong to rest when war broke out.

It was from the French Hospital that Thomas was married on the afternoon of Sunday, June 29, 1942, a bright, sunny day. Interestingly, that was the very day that the Hong Kong Americans began their journey home. The American and Japanese governments had arranged a prisoner swap, and, while most of the other British were down at Stanley preparing to wave goodbye to their American friends, Thomas was getting ready for his wedding. Many of the people bidding farewell to the lucky repatriates had tears in their eyes, and complex emotions in their heart: sorrow at the loss of friends, happiness that for some at least of their number the ordeal would soon be over, pain that they would have to remain in captivity, and hope that their turn for release would soon come. Thomas must have felt all that, and more.

For he must have been aware that what was happening that afternoon was more than just a wedding. One of the few things from the days before the war that Evelina brought with her when, almost eight years later, she started her new life in England, was this photo, torn from an old passport:

Her Portuguese nationality was her only protection against the Japanese soldiers, the one thing that might save her from rape or murder if the behaviour of the victorious army in Hong Kong was anything like what it had been in Nanking. Did Evelina seize this passport, kept in a place where she could get to it quickly, if she heard a knock at the door during those fear-filled early days of the occupation? Did she clutch it tight whenever she left the house, ready to brandish it if assailed in the street? Whatever protection her nationality gave her, she was abandoning it when she married Thomas.

The American journalist Emily Hahn was another ‘enemy’ civilian outside Stanley Camp at that time. Hahn was pretending to be Chinese, on the basis of having been one of the ‘wives’ of a Chinese poet. A friendly Japanese officer assured her that under Japanese law this marriage gave Hahn her husband’s Chinese nationality. That may or may not have been true, but it’s certain that after the wedding Evelina’s fate would be linked with that of the English community, most of whom were currently languishing in Stanley.

Why didn’t she just go home to Macao? Hahn tells us that it was still considered safe then[6] and the Government there invited all Macanese to return – the Japanese were happy for them to go, as it meant fewer mouths to feed. The situation there could have changed at any time of course, as the Japanese didn’t always respect Portuguese neutrality, and the Macau Government had to manoeuvre carefully to remain unoccupied. But for most people the security of peace, albeit precarious, would prove preferable to immediate danger and many Macanese took up the offer of refuge .

One factor in Evelina’s decision might have been the plight of the Portuguese refugees who were flooding Macao in 1942; most of them were living in over-crowded accommodation and on rations if anything worse than those available in Hong Kong. But Evelina had wealthy friends in Macao. In fact, although she probably didn’t know it, the youngest of the three Leitao sisters, her closest friends, also married in 1942. Clementina, a striking beauty, won the heart (it was said to be ‘love at first sight’) not of a baker but a Hong Kong businessman who was already comfortably situated and was later to become one of the richest men in Asia. But leaving that aside, as probably not known to Evelina when she made her decision to stay in Hong Kong, she knew she could return to Macao and expect the help of the well-off and influential Leitao family. I don’t, by the way, know if her father Antonio was alive at the time. He died relatively young of liver disease but I haven’t yet found out exactly when.

I think the real reason that Evelina stayed in Hong Kong and married Thomas was that they were in love with each other, and she was willing to risk everything so that they could stay together. Years later, when asked why she didn’t go home in 1942, she replied simply, ‘It wouldn’t have been right’.

But, given the decision to stay together, why actually get married a mere 5 or 6 months after meeting? Looked at from a purely utilitarian point of view, Lena might have seemed safer keeping her Portuguese nationality and it was useful to Thomas having someone who was not considered an enemy by the Japanese. She was working and reasonably free to move around Hong Kong, buying whatever was available with any money she had. ‘Third National’ (neutral) friends like the Swiss Robert Bauder, prominent in the wedding photo, would have been able to channel small gifts of food through Evelina without raising the suspicions of the Kempeitai (Japanese Gestapo) – some neutrals and Chinese were tortured or even executed for being too friendly to the British.

And one possible motive can be ruled out: Thomas and Lena were determined that they would not bring a child into the world under such conditions. Evelina was a Catholic, and this ruled out contraception, even if any was attainable.

I think part of the answer lies in the apparent coincidence of the town group of Americans starting their journey of repatriation on the morning of the wedding day. According to American reporter Gwen Dew, a small group of Americans were told on March 30th. they were being repatriated. This firmed up rumours that had been going around in February, and at the end of the month the Americans were told that all of them would be going home (Prisoner of the Japs pages 140, 146). Naturally the British began pressing their leaders to try to arrange a similar prisoner swap, and for a time the ever-optimistic internees were hopeful that, as the Camp ‘anthem’ put it, they would soon ‘sail away’ to freedom; my guess is that Thomas wanted to make sure that there would be no doubt about Evelina’s right to board that so-longed for repatriation ship.

But beyond all that, I think that, once again, it was a simple case of loving each other and judging that marriage was necessary if they were to live the relationship in the way they wanted. One or both of them could die at any moment, so they wanted to spend as much time together as possible, and if the end came, they would face it together or at least married to each other.

It must also be remembered that, although Thomas would have seen plenty of examples of the brutal treatment of Chinese in Hong Kong, the British had not been badly handled since the surrender. There were rapes and massacres during and just after the fighting, but since then the British had suffered humiliation and appalling living conditions, but no worse. In fact, given the Japanese suspicion of anyone who showed the British too much friendship, it might have seemed safer to both Thomas and Evelina for her to have the same status as him. She was, after all, a recent girlfriend, and one who could reasonably be expected to go back home to Macao, so why, the ever -suspicious Kempeitai might have reasoned, was she staying?

I wonder if Thomas and Evelina regretted their decision in the terrible months that began in February 1943? The Kempeitai launched a campaign against the British community, one of the first acts of which was to arrest and brutally interrogate a woman who was working for Dr. Selwyn-Clarke, who was in effect Thomas’s boss at the French Hospital. Before the end of the year some of the most important figures in the colony had been imprisoned, tortured and in some cases beheaded. Selwyn-Clarke himself faced months of brutal interrogation but never revealed a single thing about the illegal relief activities he’d been at the centre of. Amazingly, he survived the war.

But all that was in the future on that hot June Sunday when their marriage was blessed by Father Riganti, the Rector of St. Joseph’s, a man who had himself known internment – in his case, by the British, who’d arrested him when the Japanese attacked on the grounds that he was Italian and an Axis national.

The three pictures of the wedding that survive tell an interesting story. In the first Evelina and her friends are standing outside the church –St. Joseph’s Catholic Church in Kennedy Road. The name of the man she’s with, who was presumably to later give her away, is not known:

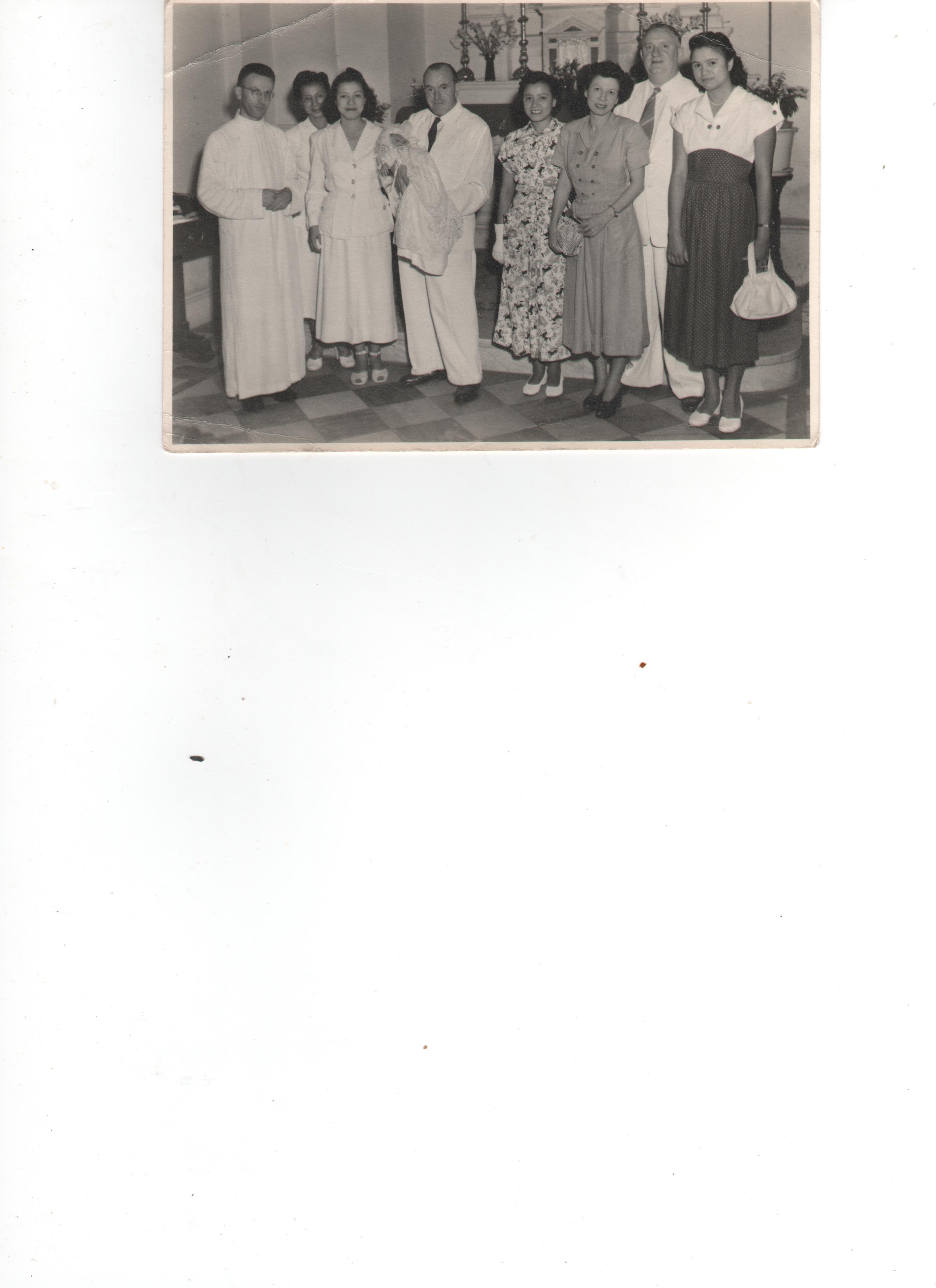

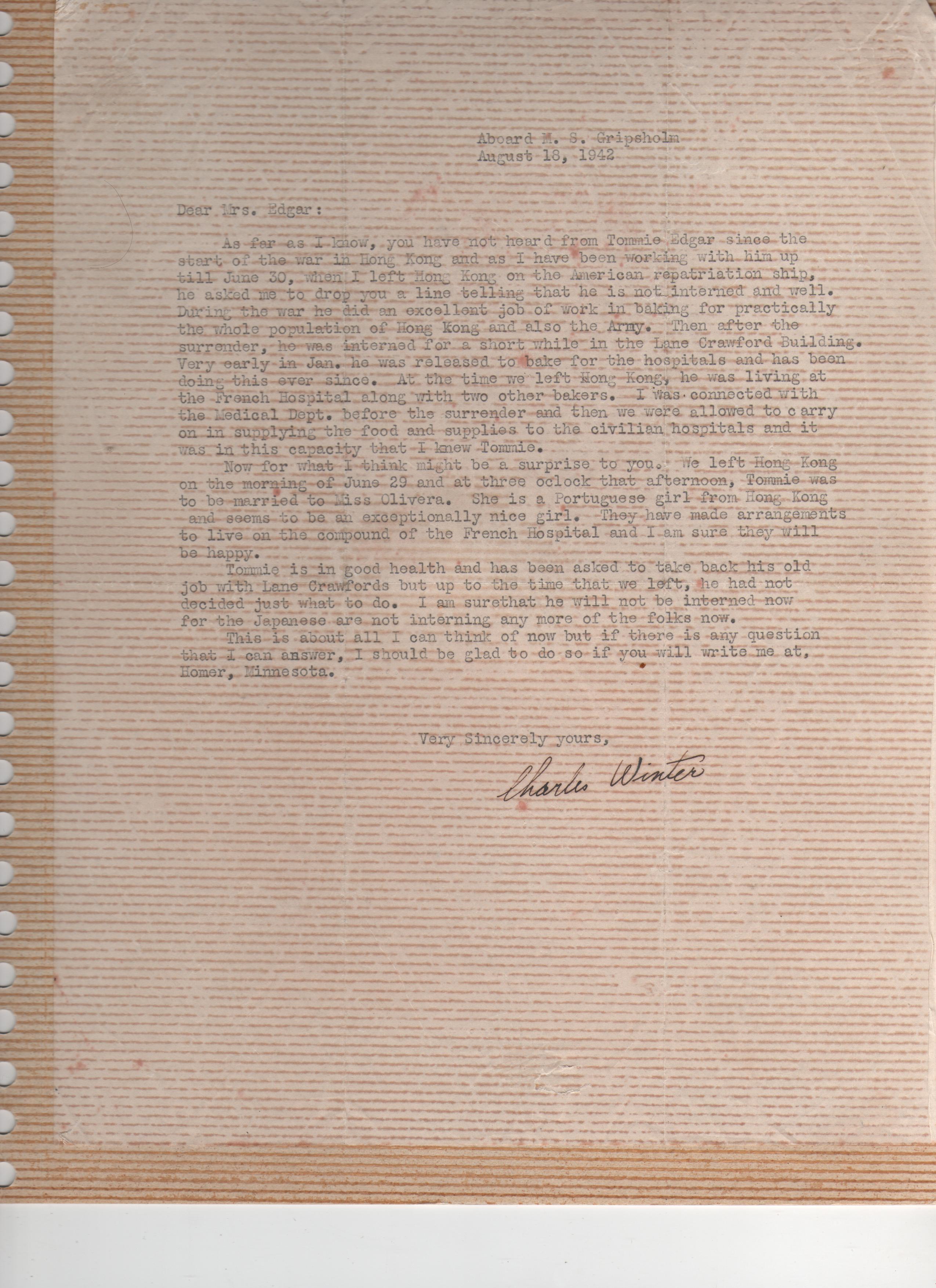

After the ceremony, the wedding party posed on the church steps:

A note on the back of one of the different—sized versions of this picture confirms that the Japanese soldier in the second row is Thomas’s old benefactor, Captain Tanaka. As Thomas was no longer under his supervision, he must have kept in touch or at least found a way of sending the Captain an invitation. He’s standing tactfully at the end of the second row, wanting to be clearly in the picture but not to dominate it.

Thomas seems in good shape after six months in captivity. He hasn’t lost much weight yet and he’s in a smart white suit with what look like good shoes. It wasn’t long after the surrender before some of the people in Stanley were trying to deal with problems caused by crumbling footwear and disintegrating clothing, while in June 1942, in the military POW camp of Shamshuipo his friends in the Hong Kong Volunteers were already suffering the torments caused by diseases of malnutrition like beri beri and ‘electric feet’ (Les Fisher, I Shall Remember, 41). But the emotional realities shown by the wedding pictures are very different.

Evelina is putting on a sweet but not very profound smile, while Thomas’s lips are only slightly raised, the merest gesture towards a sign of happiness. The other two men in the front row, Robert Bauder (second on the left, also in a white suit), and the man holding Lena’s arm in the earlier photo taken outside the church, look rather grim, while the best man, Owen Evans, is hardly smiling any more convincingly than Thomas. Only the bridesmaid on the far left and the Matron of Honour have the kind of expressions expected in the front row of a wedding party.

In the ‘happy couple’ photo, probably taken just afterwards, Thomas has abandoned any attempt at a smile; if anything, he looks angry, while Evelina’s smile has now been invaded by the ever-lurking sense of fear:

They were in love and getting married, but they had no proper home, they were hungry most of the time, and one or both of them could die violently at any time. And they had no idea when, if ever, all this would come to an end.

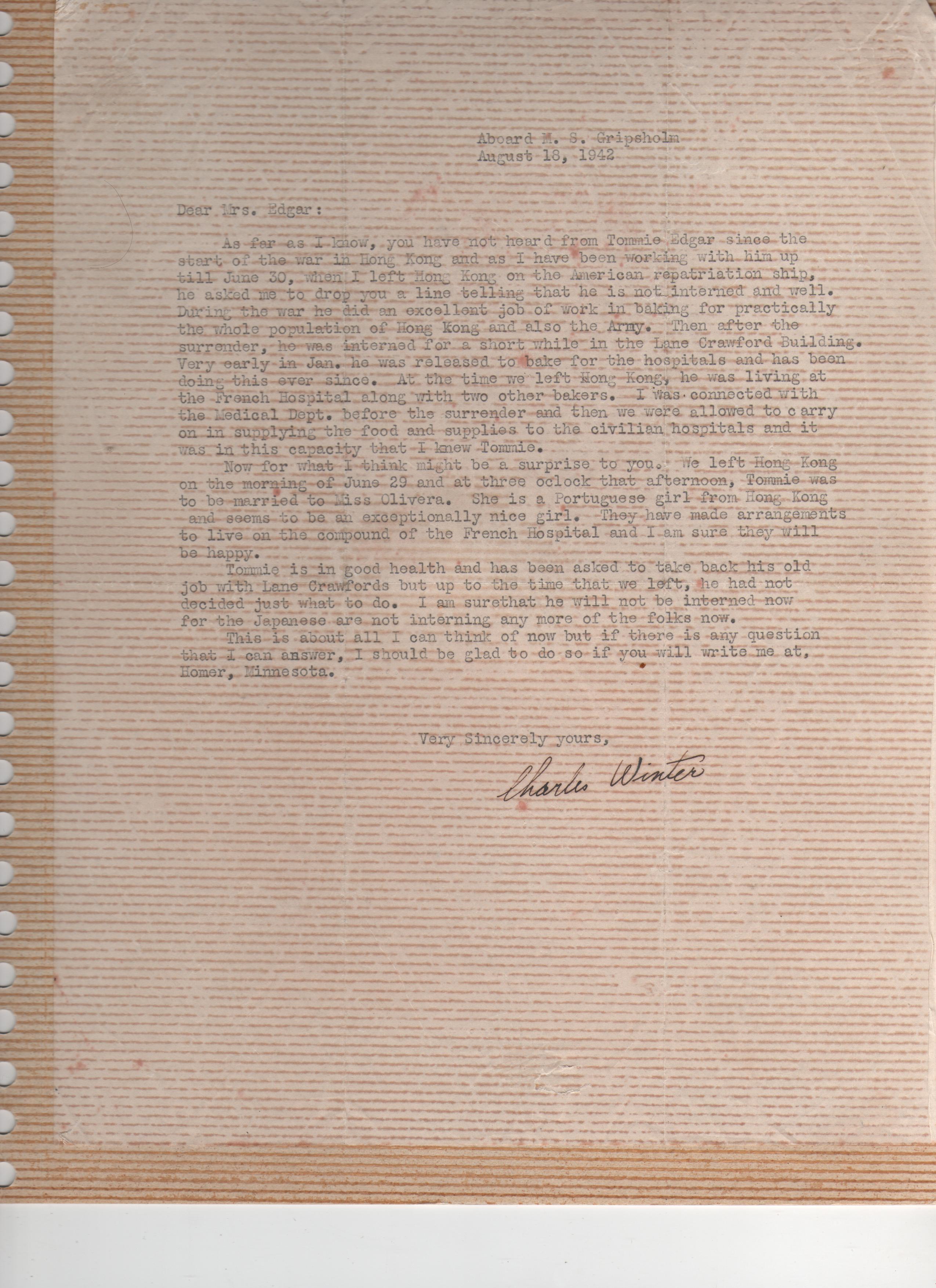

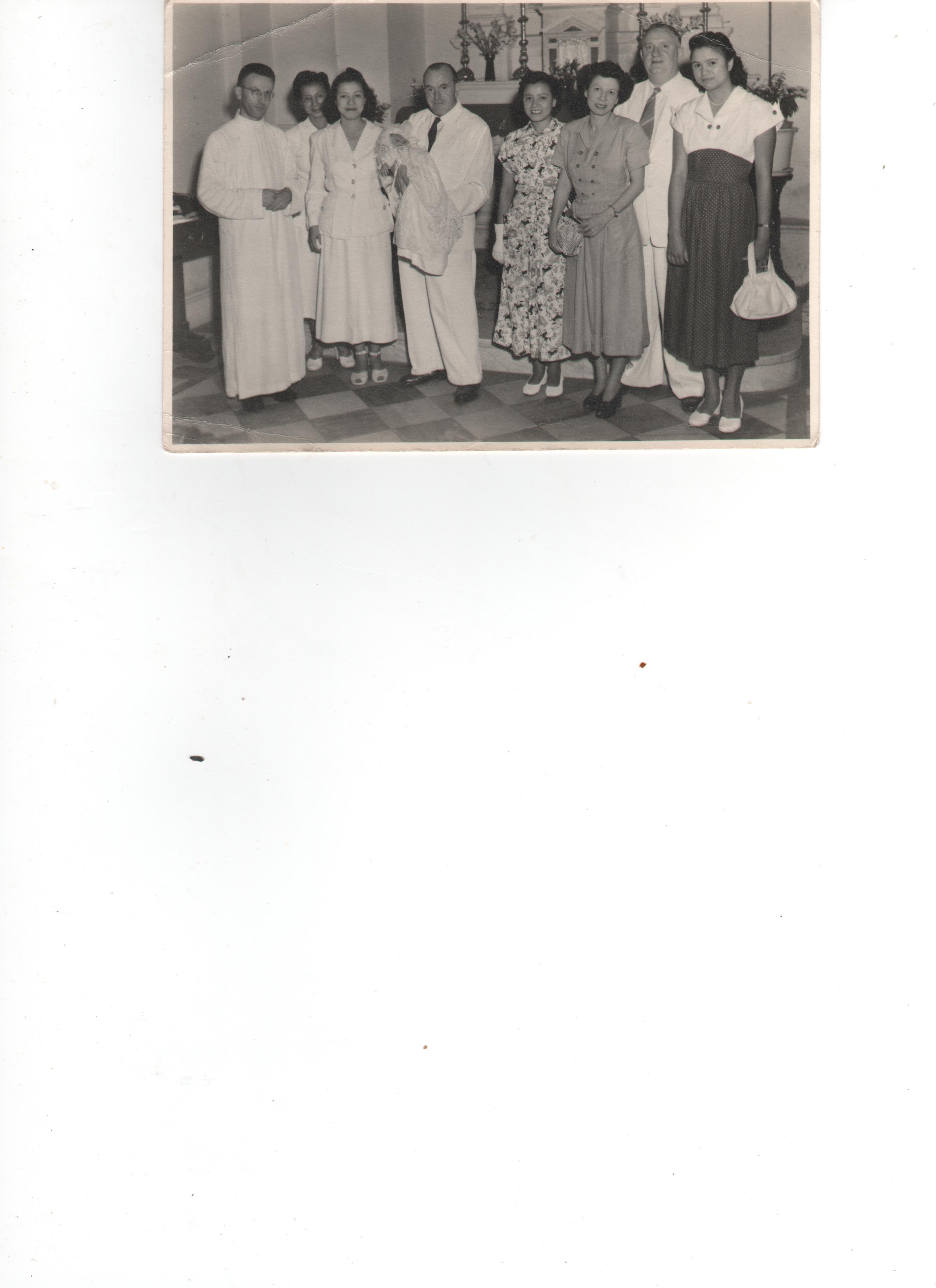

Later that year Thomas’s family in Windsor were to receive a letter from Charles Winter, Thomas’s repatriated American colleague. It is hard to imagine the relief and joy this must have brought his parents and brothers and sisters. It was the first news they’d had of him since the start of the fighting on December 8, 1941, the first indication that he was alive and unwounded.

Mr. Winters paints a tactfully reassuring picture of Thomas at work in a Hong Kong in which business was pretty much as usual. And thanks to this letter the family learnt at the same time that Evelina existed and was almost certainly their daughter-in -law!

After the ceremony was there some kind of reception, a pooling of the meagre resources available in wartime Hong Kong? There’s no doubt that Captain Tanaka – who sent the employees of the Telephone Company off to their imprisonment in Shamshuipo Camp with a bottle of whisky each – would have provided something if he could, or that friends and colleagues would have chipped in from their meagre rations. But all that’s known for certain is that Thomas and Evelina returned to the French Hospital, now husband and wife.

Footnote

About ten months later, on May 7, 1943, they were sent to join the rest of the Allied civilians in Stanley Camp; Selwyn-Clarke had been arrested on May 2 under unjustified suspicion of being a spy. They stayed there until the end of the war in August 1945. After more than three and a half years of terror and privation they were finally free.

And just over five years later, her brain and body still on fire with what had happened in the war, Evelina returned to the French Hospital to give birth to their first son. A few weeks later, the baptism took place. Robert Bauder was there again, and posed for the camera with the baby in his arms. It was the same Father Riganti who officiated.

[1]Gerald Horne, Race War!, Kindle Edition, Location 830.

[2] Horne, Location 602.

[3] Hong Kong sociologist Henry Lethbridge, quoted in Horne, Location 830.

[5] Cited in Horne, Location, 792.

[6] Marriage and Japanese law: Emily Hahn, China To Me, 321; Macao safe: Hahn, 368.